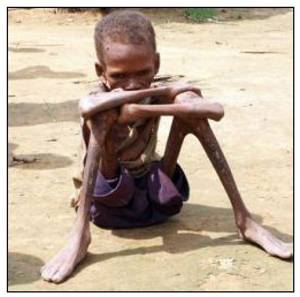

Of the 7 billion people now on the earth, it is estimated that over 1 billion suffer from hunger while approximately 1.6 billion are overweight. Both estimates are on the rise. Although world hunger is a very complex and global problem that involves many factors (climate change, water scarcity, wealth distribution, etc.), the consumption patterns of wealthy countries certainly play a role. Commodity prices are set in the global market and are heavily interdependent: wealthy citizens that can afford a certain commodity are often on the demand side of the equation, while the poor are often on the supply side. If the commodity is pens, world citizens with low purchasing power might write with pencils. If the commodity is food, world citizens with low purchasing power are malnourished, have high infant mortality rates, spend a large portion of income on sustenance, etc. The problem of world hunger actually has very little to do with resource scarcity and very much to do with inequality, wealth distribution, purchasing power and the preferences of the wealthy.

Over the past 50 years, developed countries have exported an ever-increasing amount of food, while developing countries have exported an ever-increasing amount of merchandise (see UNEP. 2009. The environmental food crisis—The environment’s role in averting future food crises). This system has proven disastrous for the local food security in developing nations, which has become dependent on the global supply chain rather than on local markets. A spike in the price of oil, a commodity which is used at every level in industrial food production, can lead to massive food shortages in developing countries. The most recent large-scale example of this was in 2008 when a price spike caused critical food shortages in 36 countries.

How are these disturbing realities related to dietary choices? Due to the culinary preference for meat and other animal products by those who can afford the market price, millions of acres of arable land in developed and developing countries are used to feed animals rather than people. Industrial meat systems, which make the daily consumption and exploitation of animals possible, can afford to pay higher global food prices than the starving citizens of poor countries. In other words: meat is not only a luxury for the rich, it is also the source of much suffering for the poor. According to a 2009 study by UNEP, the United Nations Environment Program, “… the loss of calories by feeding the cereals to animals instead of using the cereals directly as human food represents the annual calorie need for more than 3.5 billion people.” From a world hunger perspective, reducing global meat consumption by a third could alleviate the crisis without increasing agricultural output. In addition to the global issues concerning world hunger, there are countless case studies that illuminate the present situation. As one example, consider North Korea. In 1997, despite extreme food shortages, the country exported around 1000 tons of maize to a Japanese poultry operation. Or take Ethiopia, which exported food to the UK during the famine of 1984. These two extreme examples involve country-wide famine and the global market, but the same is well documented within countries. Consider the Indian poultry industry. Low-priced grain is used to feed the industry, which grew from 300 million birds in 1993 to 800 million in 2000. The target of the intensified production is India’s expanding middle class, which leaves even less for the malnourished and starving (see CIWF. 2004. The Global Benefits of Eating Less Meat).

As an example that is closer to home, consider that at 270 pounds per person per year, Americans consume 167 pounds more than the global average, and rank number two after Luxemburg. The poultry, beef and chicken that fill that demand are fed primarily corn and soy, at an enormous caloric loss. Around 80 percent of the corn and 50 percent of the soy grown in the U.S. are used to feed animals. Beef that is imported into the U.S. has a direct rainforest foot print, which is comprised of land cleared for grazing and soybean production. If the rest of the world were to adopt an American-style diet, which is an aspiration highly correlated with an increasing level of affluence, we would need the resources of 5-6 earth-sized planets.

There are numerous other ways in which the consumption of animals contributes to world hunger. In the FAO report Livestock’s Long Shadow, it is estimated that the livestock industry contributes 18 percent to global greenhouse gas admissions, which is greater than the transportation sector (see FAO. 2006. Livestock’s Long Shadow). The negative effects of climate change on world wide agricultural output are well documented and future predictions only continue to worsen, even without accounting for unforeseen environmental catastrophes. Water scarcity is yet another component of the world hunger crisis that could be abated by a worldwide change in dietary preferences. The U.N. estimates in the FAO report Livestock’s Long Shadow that 64 percent of the world’s population will live in water-stresses regions by 2025. In the same report, it is asserted that livestock production contributes an estimated “55 percent of erosion and sediment, 37 percent of pesticide use, 50 percent of antibiotic use, and a third of the loads of nitrogen and phosphorous in freshwater resources.”

This is a short description of an immediate and massive problem. If more convincing is needed about the harmful effects of meat production, simply search the Internet for “effects of meat production” and you will see that the evidence is overwhelming, and not only from the perspective of world hunger. There are also the issues of ethical treatment of animals, personal health and a host of environmental issues. If the past gives any indication of future trends in resource use, little will change to help the current crisis. Weakened from centuries of colonialism and suffering from internal problems, the governments of many developing countries lack the power to enforce meaningful policies to combat the purchasing power of wealthier countries. Many citizens of wealthy countries are aware of the hunger crisis but feel powerless. Consciously changing one’s diet is one way to directly contribute every day and generate discussion about the issue. Lifestyle choices is where the rubber hits the road. The solution to this crisis can’t be purchased though ethical consumerism or fixed by voting for the best among bad political candidates. Although as individuals we have little to no influence on the political situation that promotes such injustice, we can choose to make a difference every time we take a bite. Go vegetarian/vegan (or at least consider dramatically reducing meat consumption) for yourself, your community and the world community!

Below are few excerpts from reports that are relevant to the topic of dietary choices and world hunger:

In the second half of the 20th Century, worldwide meat production increased roughly fivefold; per capita consumption more than doubled. Even though the industrialisation of farming has allowed vast numbers of animals to be reared in relatively small areas, those kept in factory farms cannot forage for their own food or live on scraps or waste products—as was traditionally largely the case. Consequently, massive areas of land are given over to growing crops to feed them. Livestock production has become the world’s largest user of agricultural land.

– Executive Summary, “The Global Benefits of Eating Less Meat,” CIWF (Compassion in World Farming)

The livestock sector emerges as one of the top two or three most significant contributors to the world’s most significant environmental problems, at every scale from local to global.

The livestock sector may be the leading player in the reduction of biodiversity, since it is the major driver of deforestation, as well as one of the leading drivers of land degradation, pollution, climate change, over fishing, sedimentation of coastal areas and facilitation of invasion by alien species.

The major sources of pollution [water] are from animal wastes, antibiotics and hormones, chemicals from tanneries, fertilizers and pesticides for feedcrops, and sediments from eroded pastures.

– Executive Summary, “Livestock’s Long Shadow,” FAO (Food and Agriculture Administration of the United Nations)

The global production of cereals (including wheat, rice and maize) plays a crucial role in the world food supply, accounting for about 50 percent of the calorie intake of humans. Any change in the production of, or in the use of cereals for non-human consumption will have an immediate effect on the calorie intake of a large fraction of the world’s population. As nearly half of the world’s cereal production is used to produce animal feed, the dietary proportion of meat has a major influence on global food demand (Keyzer et al., 2005). With meat consumption projected to increase from 37.4 kg/person/year in 2000 to over 52 kg/person/year by 2050 (FAO, 2006), cereal requirements for more intensive meat production may increase substantially to more than 50 percent of total cereal production (Keyzer et al., 2005).

– “Food Crisis” 2009, UNEP