That the American public is woefully misinformed about what is happening to our planet is no secret. During the July heat wave, the number of those claiming to believe in climate change rose to 70 percent, which is a 5 percent increase since March. The key word in that sentence is believe, which is a very different verb than understand. “Believe” implies a level of choice on the part of the observer, as well as a high level of uncertainty. “Understand” in that sentence would indicate a decoupling of the perception of weather as the sole indicator of climate change. But the sentence doesn’t say that, and it shouldn’t. Pleasant fall weather will be accompanied by lower energy bills, as well as a predictable decline in public interest and media coverage of the critical topic. Or perhaps not. Maybe the fall and winter will be stormy and frigid, so that instead of sweating out a power failure we are scrambling for blankets. In any case, the Citizens Climate Lobby (CCL) will be in the thick of it, advocating “political will for a livable planet” with a message backed by an astounding volume of scientific and world literature.

On Sept. 2, the Nashville chapter of CCL met at Buttrick Hall on the Vanderbilt campus. The group hosts meetings on the first Saturday of each month. Each meeting consists of two parts: a conference call with the national chapter and other local chapters, as well as a work session. For those interested, more detailed information is available via a bimonthly national conference call. I attended my first meeting on Sept. 8. The guest speakers that day were the renowned climate scientist Dr. Veerabhadran Ramanathan from the Scripts Institution of Oceanography, as well as David Turk from the U.S. State Department.

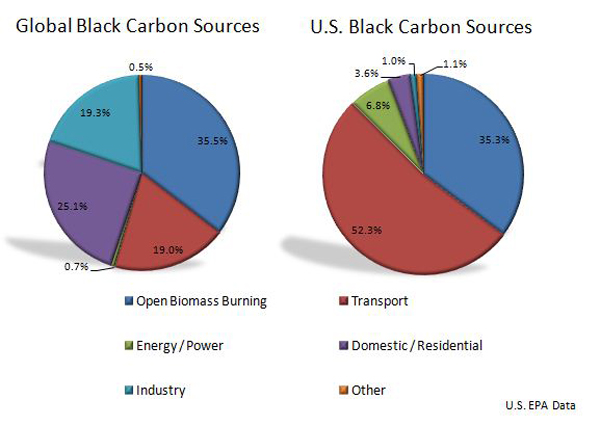

The focus of Dr. Ramanathan’s talk was “black carbon”, which is the particulate matter formed by the incomplete combustion of solid or liquid fuels. The sooty substance ranks closely after CO2 as a climate change agent, and is a major target for global reductions. The primary sources of black carbon are shown in the graph below.

Unlike CO2, which has a long atmospheric life, black carbon only remains in the atmosphere for a period of days or weeks. This means that immediate reductions in black carbon produce immediate results. The substance acts as a climate change agent both by absorbing sunlight, as well as by darkening surfaces that would normally reflect light back into the atmosphere. Certain types of black carbon also affect cloud formation, creating conditions where precipitation from larger clouds is enhanced, while precipitation from smaller clouds is reduced. The end effect is that dry areas become drier and wet areas become wetter.

In the US, diesel is the main culprit. In developing nations, cooking is a major source of black carbon. In one Indian case study cited by Ramanathan, black carbon reductions as high as 80-90 percent were possible with better cooking technology. A proposed solution is to link these reductions with carbon credits, which would provide a monthly average of 6 dollars per home for nearly 160 million families. As an additional bonus, better technology (which is only a cooking chamber and a solar fan, as opposed to traditional mud) would eliminate the health problems caused by indoor smoke.

Below are the responses from the Q&A session. Questions came from chapters all over the U.S., and were answered by Dr. Ramanathan (paraphrased here)

1. What is the impact of solid fuel cooking on the Himalayan glaciers?

Black carbon becomes trapped in the snow, causing it to darken. This accelerates the melting process.

2. Is solar cooking a good solution for developing nations? (my note: why not all nations?)

Solar cooking would solve almost all of the problems, but the women who cook in villages also work in fields. When they rise it is dark out, and when they return it is dark out.

3. What exactly is the new cooking technology?

The new stoves contain a heat chamber and a solar fan, which provides a steady supply of oxygen to the flame. This results in nearly double the fuel efficiency, as well as up to an 80 percent reduction in particulate matter (black carbon).

4. Did I hear you correctly that when compared with CO2, black carbons contributes 50 percent to climate change? How much of an impact could the stoves have?

Great question, 50 percent refers to all non-CO2 pollutants, such as methane, nitrous oxide, ozone, halocarbons, as well as black carbon. Black carbon is number 2 after CO2. Among the sources of black carbon, stoves contribute between 25 and 40 percent, so they are a major source.

And finally, David Turk spoke briefly about the voluntary Climate and Clean Air Coalition from the US State Department. The group focuses on large-scale projects to reduce non-CO2 sources of climate change. As of February 2012, the coalition was comprised of 6 countries and UNEP. Today the coalition has representation from over 20 countries, as well as the World Bank and various NGOs. A scientific panel guides the group’s progress in the following initiatives, among others:

• Diesel

• Oil/gas

• Landfills

• Brick kilns

The scenario: the world and scientific community are unanimous in the understanding of how our planet is changing. The American public is grossly misinformed about what is likely the most important issue that we collectively face. The solution: be part of the discussion. Don’t let the political will for action on climate change come about as the result of conditions that can no longer be ignored.