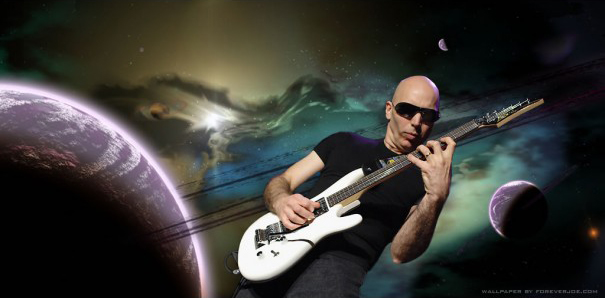

Joe Satriani performs at Nashville’s War Memorial Auditorium. Photo by Shawn Jackson.

In the annals of music history, few people have contributed as much as Joe Satriani. A legend’s legend, Satriani’s love affair with music began in the 1970s with the death of Jimi Hendrix, deciding to study music under jazz influence Lennie Tristano. Sharing his knowledge as a guitar instructor and teaching some very famous students how to play—including Kirk Hammett, Charlie Hunter, Steve Vai, Alex Skolnick, Kevin Cadogan, Andy Timmons and Larry LaLonde to name a few—his innovative playing techniques and musical style have branded him as a virtuoso. With 15 Grammy-nominations, 5 live albums, 4 compilation albums, and now 14 studio albums with the recent release of Unstoppable Momentum, Satriani has proven that he is a force to be reckoned with. His collaborations include works with Alice Cooper, Brian May, John 5, the Steve Miller Band, Blue Öyster Cult, and his own supergroup project Chickenfoot and tour project G3. He has also worked with several music instrument companies to create signature instrument items, further pushing the envelope in music. A rock ‘n’ roll demigod, Mr. Satriani was kind enough to talk with the Pulse about his Nashville appearance at the War Memorial Auditorium on Sept. 17.

Murfreesboro Pulse: Mr. Satriani, thank you for chatting with us. It’s an incredible honor. Now, Unstoppable Momentum is your latest album. In terms of both inspiration and emotion, where were you when you conceived the album?

Joe Satriani: Well, I was all around the world, I guess. I mean technically, I start thinking about making new records kind of like once I finish the one before it. I feel the need to just kind of move forward. Last year, I did three G3 concerts on three different continents, we did a bunch of Chickenfoot tours and some Montrose benefit/memorial shows. I guess by the time I came home last October, I had about sixty pieces of music to sift through that I had been writing.

MP: Did you say sixty?

JS: Yeah.

MP: Oh, wow (laughs).

JS: Yeah, and some of them were completed, some of them were just in their infancy. Quite a few in-between . . . and that process of editing down is my most important part. That’s where the conception of the record happens, because I purposefully keep the idea of the album [as a whole] out of my mind until the last possible moment. That way I can compose freely, without any restrictions of style or logistics. That’s what it’s all about when you make a record. It’s just how, and where, and who, and how much time have you got, and how much money have you got, and that sort of thing. And I don’t like that to affect my writing, so I spend all that time while I’m touring, coming home, and resting writing material. And then two months leading up to a studio session, that’s when it’s really crunch-time. And I try to figure: “Are there twenty or fifteen songs that really stand out, or belong together? Do they represent a new direction for me that I’m excited about?” I guess what clinched it was that I had started writing this song a few months earlier called “Unstoppable Momentum” that was really about just putting a song to that feeling inside of me that I get—that inspiration—that makes me so excited about my guitar, my pickups, my strings, my amps, my pedals, the chords. You know, what can I do with chords that no one’s done before? What kind of harmonies can I put together that no one dare try? How can I make it sound really easy and fun to listen to? It’s those things, and I’m always excited about trying to find a spot for a beautiful melody. So the song is really about that. I guess it’s about me and my natural predilection, I guess.

MP: It seems that with your work, you’re continuously stretching the limits of creativity. Where do you feel that this is going to take you in the near future? Where do you see yourself?

JS: Well, I have no idea. The flip-side of what I just told you is that now I’m out touring. So I’m in this period where I just finished the first nine weeks of playing over in Europe. And I’ve kind of allowed myself not to be tied down. I’m not even thinking about another record in concrete terms. I’m enjoying being like a free spirit. Like a guy who just wants to play a guitar and run around onstage, and doesn’t have any responsibilities to think about another record. So where I’m going I don’t know. I’m just really excited about being in the playing phase right now, in the performance part of the never-ending circle.

MP: That brings us to a question from one of our readers submitted. Local reader Cody Moffitt wanted to ask: “Do you ever hit plateaus when you’re playing or writing, and how do you overcome them?”

JS: I think so. I think it’s natural. I think there are those big ones, where you start to write a song, and then all of a sudden you don’t know where you’re going to get the rest of it. You may find it ten minutes later, ten days later, ten years later, twenty or thirty years later, that it suddenly makes sense to you. I’ve certainly had songs do that—take a decade or two to make sense. And sometimes it’s just because you gotta meet the right people, or you have to experience some more stuff around the world. Or in life. And suddenly it comes into perspective. It’s sort of like a comedian learning exactly how to tell a joke, or a writer finally figuring out how to approach a particular subject and create a wonderful story around it. And so with the musician, it’s not all about “I think about it now, it works, I put it on a record and off we go.” Sometimes, they take some time. So there are those kinds of plateaus. And then I think the micro-plateaus are inevitable. You’re onstage, you’re playing, everything is going great, and suddenly you’re going, “Wow, I hit a brick wall.” It could be physically, you know. That day, you’re tired ’cause you didn’t get any sleep, or you got a stiff neck from sleeping on the bus or something. And then you feel like “I can’t physically get over this plateau that I’m on.” I’ve heard a lot of words of wisdom from different people I’ve worked with, and one of them sticks with me very often. Which is something that legendary producer Glyn Johns said to me once. That it wasn’t my job to figure out or dictate what people should like about what I was doing. He said, “Your job is just to play. To create and play music. And don’t ever worry about whether people are going to like it or not. In the long term or in the short term.” And that echoed something that [late jazz pianist] Lennie Tristano taught me many years ago when I was still just a 17-year-old guitar player. Lennie had said to me that, “Kids in the suburbs had a disease called the subjunctive disease. Which is they’re always worrying about what they should have done, could have done, and would have done, and they never do what they want to do.” Of course, this was all related to improvisation—he was a bebop wizard, and just a giant of a musician. But the two pieces of advice go together very well. And it relates to this idea of plateaus, and whether or not you should even worry about it. It’s not really the artist’s position to worry about how the plateau gets recognized, or how it impacts the audience. We should just keep moving forward. No matter what. That’s how you get over the plateau. You just not think about it.

MP: I see. In addition to being a guitar virtuoso, you’ve also taught some very famous students as a guitar instructor. We’re not even going to bother listing off the names because of how long that list is, but as such a celebrated guitar instructor, do you find yourself wanting to help other musicians learn? If so, how do you approach that without hurting their feelings?

JS: My experience as a teacher has always been that if a student comes in to learn something that it’s gonna work out really well. There’s a lot of self-discovery that goes on there. But if a student comes in with an an overall desire to become rich and famous, that’s gonna be a problem. Or if they haven’t really taken stock of their abilities, if they’re asking for something that they can’t possibly perform, then there’s gonna be some problems. The typical thing would be someone who doesn’t know how to play a scale wants me to turn them into Yngwie Malmsteen. The people I was lucky enough to teach that went on to be successful all have very different personalities and varied amount of physical talent that they were drawing upon. A young Steve Vai or Alex Skolnick had incredible technique, being able to play almost anything physically. Kirk Hammett was pretty much almost the same way. I had other players that were either real beginners or had no interest in like shredding or anything. David Bryson from Counting Crows was all about chords and writing music. The scale thing was kinda cool, but he really wasn’t interested in soloing at all. It was very interesting to redirect lessons towards that space. Young Charlie Hunter, who has gone on to become a jazz innovator, he started out also not being into the whole shredding thing at all. He wanted to know more about chords and rhythm, and the music theory behind it. He wasn’t interested in the flash aspect of it, really. You can see how each of these guys wound up turning into such different musicians, but they are unique. They brought out into the music world some very interesting and unique personalities. It’s their own, basically. They’re bringing out their true personality through their music. You know, usually when lessons go bad because people get their feelings hurt, it’s generally because they come in with misguided expectations about the teacher.

MP: That kind of brings us to our next question, which you may have answered in part. We were going to ask “What mistakes do you see a lot of young musicians making, and what advice would you offer,” but from what we’ve gleaned from you, all students should keep an open mind. Is there something you would like to add to that?

JS: You know, I think that young musicians and experienced players like myself, one thing that we all have in common is that we all make mistakes. Every night. All of us do. We forget. We space out. Our finger goes to the tenth fret instead of the ninth. It’s kind of humorous. I don’t know what it is. But humans just make mistakes. We do. Things don’t go as planned. That’s OK. So, the first thing I would say is don’t worry about the mistakes. That’s not what turns people off. I think that what turns people off are boring performances. Performances that are not uplifting. Records that don’t transport them anywhere, that don’t help them in life, you know? All of us use music for good times and bad times. We need that accompaniment to be the soundtrack of everyday existence. So when you keep that in mind, you realize, “Wow, this whole thing about making a mistake here and there is OK.” The big, real mistake is not really trying to be original. But it’s a bit of a problem for the musician starting out. It’s very easy for me to spit out that advice because I have a worldwide audience that’s accepted my eccentricities. I can put out records. But I clearly remember up until when I was thirty, the pressure was on me as (an unknown, working guitar player) to actually imitate other players. I did not get work by being original. I got work by being able to emulate or imitate the most popular guitar players. That’s how all of us get work. Playing clubs, parties, dances, whatever kind of gig is out there. It’s being able to play a huge repertoire of music, and being able to replicate all the different players from all these past decades. And that takes a lot of time, and it’s a problem. When do we get to work on our own stuff? So that when someone comes around and says, “Hey, what have you got that’s special?” you’ve gotta say, “Wow! Haven’t had time. Too busy imitating Steve Vai and Eddie Van Halen so I can get work and pay rent.” I don’t like to say it’s a mistake, but I like to remind young players that yeah, you somehow gotta figure out time to develop your own stuff and an original sound. That’s what people buy tickets for. They’ll come to see you if you’re something special. Not if you’re a clone of somebody else.

MP: On the topic of reinvention, how much room for improvement is there with instrument technology? Do you think that the majority of what’s been figured out with a guitar has already been invented? Do you feel that there’s always room to grow? Where do you stand with basic instrument technology?

JS: I think that if you look at a new player on the scene, like Tosin Abasi, you go, “Oh my God, this guy’s just taken a whole different way of playing out in a direction no one thought of” . . . let’s say when they were listening to me on my six-string, two-hand tapping stuff, or earlier versions of that. Or Wishbone Ash, guys like that. In the fifties, there were a lot of acoustic guitar players doing two-hand tapping stuff. But Tosin, and that band Animals as Leaders, they’ve taken it to a whole new level with their stuff. I think that’s a good example of what can happen. I would mention at the same time, you look at someone like Jack White and go, “Wow, here’s the total opposite approach of someone like Animals as Leaders.” Where Leaders and Abasi are looking way forward and saying, “What hasn’t been done before?” technically, as well as musically. Or, “What can we achieve musically that is completely brand-new?” and they’re willing to sacrifice all their time to learn an entire music technique to play a seven- or eight-string guitar. But it’s, to me, it’s equally valid as artists that lean heavily on style, entertainment, and show. I mean, it is showbiz after all, right?

MP: Right.

JS: And bringing stuff back from the past. To me, it’s just as equally valid. So, whether it’s Jack White or Tosin Abasi, to me it’s equally important and artistic. It’s fun to listen to. It’s cathartic to listen to if that one song hits you the right way. I think its important never to worry about things like where it’s going, or can anything new be done. I mean, think about it: When Franz Liszt was alive, this guy could play piano like nobody else. But the world of piano playing didn’t shut down after he hung up his hands (laughs). You know? We’ve moved on. There’s always new stuff to do, even in the days of an incredible virtuoso, who could not only play but had physical traits that were so outrageous. There were other players who brought new things out. There will be new Einsteins, there will be new Beethovens, new Chopins, Liszts. And there will be new Van Halens, and so on, and so forth.

MP: Being near Music City, I think I can say we appreciate all of those inspirations. We have another reader question, this one from Blake Dellinger. Blake asks “You once played for Deep Purple after the departure of Ritchie Blackmore. What was that experience like, and what are your thoughts on Deep Purple’s current incarnation?”

JS: Well, getting the call [in late 1993] to replace Ritchie Blackmore was a very short one. My manager called and said “Hey, Ritchie Blackmore has abruptly left. He’s got a tour in Japan in one week. The band has asked if you’d like to play,” and I said, “There’s no replacing Ritchie Blackmore. Don’t be ridiculous.”

MP: (Laughs)

JS: (Laughs) And I hung up the phone immediately. That’s insane, you know? And then, 30 minutes later, I was thinking, “That’s crazy, how could you not say yes to play with the original lineup of Deep Purple?” [Editor’s note: Joe means the second and best-known lineup, active in the early 1970s; the original version of Purple lasted from 1968-1970.] That’s the one that I grew up listening to. So I called my manager back and asked, “Did you tell them I said no?” and he said “No, I knew you’d call me back.” So, I wound up getting some cassette tapes of their last show, on half of which I think Ritchie had already left the stage, so there was no guitar. But I had to learn the current show. The lights, everything, the staging, was all built around this current set list. The most exciting moment for me was when we did this one rehearsal in Tokyo, and I was blown away because they sounded exactly like Machine Head, the [1972] album. And it was exactly like I had walked into the album and I was just there, replacing Ritchie’s guitar. Each of the guys in the band sounded exactly the way they did on the album.

MP: Almost like stepping into a time machine.

JS: It was crazy! Yeah! And they were fabulous musicians to play with. They were great in it together. They were very unique and interesting people individually, and they had this thing where they could really get together and become a band, like you would just count off, “One, two, three, four,” and suddenly they were all there. It was very powerful and uplifting for me to play with them. It was a bit frightening. You know, that first tour was only about three weeks long. Most of the time I was really focused on recalling the show correctly. I had a lot to memorize, and I hadn’t played Deep Purple songs in years. I had been a solo artist for quite a while so I hadn’t really thought about it. The last time I did that kind of thing was when I played with Jagger. But we did a lot of new things with Mick. That was back in ’88. So, it was a lot of fun. Then, a couple of months later, I played with them for two months. We did a two-month European tour, and I think that’s when I really grew into the position. But ultimately, in my brain, I kept hearing Ritchie’s guitar sound, and Ritchie’s brilliant stylings of playing. And I kept thinking (laughs) “Who is this Joe Satriani guy? What’s he doing here?” I just always felt like I’d be haunted by Ritchie’s legacy. I remember telling [Purple bassist] Roger [Glover] that “I don’t think I can do this. I’m not the guy you need, someone who will come in and revamp the band with you.” Because that’s what they wanted. They wanted to continue, but they wanted to continue fresh. They didn’t want someone to come in and be Ritchie. So, perhaps I was too much of a Ritchie Blackmore fan. I just couldn’t figure out how to get myself out of it. I was also feeling like I was the luckiest guitar player in the world: I had a solo career and Sony Music and Epic Records support me with whatever I do. I just couldn’t figure out why I would be turning my back on my fans and all the people who helped me get here, just to realize this rock and roll fantasy. So, yeah, that’s how that happened. And during that conversation, Roger had brought up Steve Morse, and I had just thought that would be so amazing. I knew Steven, and he’s such a brilliant player. He’s an amazing composer, and he writes just about every genre, so I thought I had to hear that. It turned out to be a very wise choice because it was exactly the kind of different guitar player they needed, rather than getting maybe a British player who was going to just do what Ritchie did. I’ve never met Ritchie Blackmore, but I figured he was happy that they went with an American player that has such a rich, American musical heritage behind him. Because that’s what he brought. He brought a rich, American musical sound to the band.

MP: Let’s talk about your book. Scheduled for a release in April 2014, it’s titled Strange Beautiful Music: A Musical Memoir. Could we get you to offer a few details about the book? What should the fans expect from this introspective on your creative process?

JS: It’s an interesting thing. I never thought I would do a book, although I started working on a biography years ago, and it went nowhere. I just found it too unnerving, to tell you the truth. To sit down, and start writing about your past. It kinda drove me crazy. And then out of the blue, Jake Brown called me, an author who has been writing these books. I think he’s got about thirty or so published books out, all centered around musicians, engineers, producers, etc., sometimes focusing on just the catalog, meticulously going through everything about the catalog, and some other stuff that’s more interview-oriented or more biographical. And he came to me with the idea of “Let’s do a book,” and we started talking about my crazy experience of trying to write an autobiography, to which he said “Let’s not do that. Let’s start out just talking about the music.” Because he was thinking, and correctly so, that the fans are really interested in the work, the catalog, and everything that went on in creating those records—song by song—and the people who helped me create them. Not only the technical aspects, but also what was the creative process, what were the funny stories, the unusual anecdotes that surround these records that continue to sell and are a part of my catalog? And now I guess I’ve got 14 studio records to talk about. So we went through this process where he interviewed me just forever, it seemed, just about every single record, every song on the record. Then he went and interviewed all of my producers, co-producers, engineers, all the musicians, and also players that wound up contributing to the live recordings. Just to get the full background. And of course the record companies that were such a great, creative, supportive force in my life and still remain a credit today. So the book is filled with that, it’ll be filled with lots of crazy pictures of course. I’m really worried that the book tour is going to be something strange. I know the book is going to be great, because it’s almost all finished and I’m feeling really great about that. But my manager mentioned about going on a book tour, and I thought (laughs), “Oh my God, really? I’m going on tour and I’m not playing?” I thought that was frightening. I’m kind of a shy, retiring type. Put a guitar on me, and I become something else. But if you put me in a bookstore behind a table with a stack of books, I’m not quite sure what’s going to happen.

Tickets for great shows, such as Satriani’s Sept. 17 appearance, can be found at the War Memorial Auditorium’s website. Also, be sure to check out Satriani’s site as well.

Photo by Shawn Jackson