Oaklands Mansion.

(Top) The piano in the front parlor at Oaklands Mansion

Words in song have power: the power to create or destroy, power to define a generation and move history. Lyrics are not idle. They are meditative and have the power to convey the way we think and feel. Perhaps over the generations, we have one commonality—“We feel the way we feel because we think the way we think!” Good or bad, this emotional connection has the power to connect one generation to another.

In America, the decades between 1850 and 1870 were perhaps the most profound in clearly defining and blending musical styles into what would later become America’s popular music. The antebellum period’s minstrel tunes, parlor songs, marches and reels would blend with hymns, carols and spirituals. American musical styles would move from Classical European and evolve into identifiable sound fusing influences that migrated from Scotland and Ireland, the Italian, French and English. Tunes written for the piano, brass instruments and drums, along with string instruments like the banjo, guitar and fiddle, would reflect the progress and expansion of this era in American history.

Prior to this time, published music was expensive and rare except in the parlors of the elite. Up until the 1850s, music was not characteristically American, as we had not found our own musical voice. With the emergence of melodious songs from Stephen Foster, the “father of American popular music,” the American culture began to convey its heartfelt emotions and sentiments in song. Songs such as “Camptown Races,” “Jenny With the Light Brown Hair,” “Oh! Susanna” and the warm sound of “Beautiful Dreamer” were favorites of both Northerners and Southerners, eclipsing every other composer of that era.

Although Foster’s sheet music may have appeared on the melodeons and pianos of Murfreesboro’s privileged, the lyrics may be considered derisive both then and now. In many ways, having come out of the minstrel tradition, these songs began to unravel the racial bigotry and the tragedy of slavery embedded in antebellum America. Perhaps it was one of the reasons that there was such division in Murfreesboro about succession from the Union. In the election of 1860, both the state and the county cast their votes in favor of the Constitutional Union Party and John Bell. In a referendum, Murfreesboro and Rutherford County voted against succession. R. S. Northsutt published in the Rutherford Telegraph this staunch Union response: “Under the circumstances that now exist, there is no cause whatsoever for disunion, and he that favors it can be guilty of nothing short of treason to this country.” In addition, he made known this motto originally credited to Daniel Webster: “Liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”

More than any other influence, the very first spirituals inspired by African music elevated spirits and enlightened faith and hope. In the fields, their blissful, sometimes mournful work songs were expressive, sending implied hidden messages to fellow slaves. Songs like “The Gospel Train” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” all referred to the Underground Railroad. Syncopated, segmented melodies, along with “shouting” gospel lyrics, clapping, foot tapping, stomping and dancing, would later influence modern rock ’n’ roll styles of the 1950s.

Big dreams, small dreams, such a marginalized existence; a field slave could work all day, every day. Cotton pickin’ produced achy backs and rough hands scarred from years of picking bolls. But then the songs emerged audaciously, perhaps from an attitude of accomplishment driven by a victorious battle for freedom.

One old fella’ once said, “Ya’ just get a little bit, not enough to feed ya’ family, but ya’ do what ya’ can to get by. It really matters to do a good job for my massa. No rocks in my cotton bag!”

Wisely, an ole granny once surmised, “Ya’ can learn a lesson about life from a cotton boll. In God, you are soft and safe, out of harm’s way—all wrapped up in the things that prick your life!”

The American Civil War had a profound impact on America’s music, spurring the publishing of patriotic songs on both sides. The North and the South had their own versions of “Dixieland” (Dixie); the song remains a vivid example of lingering Confederate mythology and Southern culture. Both Yankee and Confederate soldiers carried small songbooks in their leather satchels: The Guiding Star Songster, 1865; Songs of the Soldiers, 1864; and Beadle’s Dime Pocket Songster, published between 1865 and 1867. The war brought the use of brass instruments and drums into common use. Also, the migration of African-American slaves brought cultural diversity, mixing musical styles across the land.

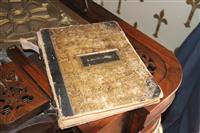

This songbook, circa 1860, belonged to Adeline Maney, mistress of Oaklands Mansion

The antebellum era was filled with turmoil and social upheaval. The issue of states’ rights and slavery became contentious, with a divided community here in Murfreesboro. Our central location, accessibility to railways and good roads made the community desirable for both the North and the South. Notably, in the 1850s and 1860s Rutherford County had grown prosperous, becoming a leading producer of corn and cotton.

Although Murfreesboro’s affluent were completely Southern in ideology and mannerisms, most had become acclimated to the finer things in American life both in fashion and music. Often, the women would adorn the balls held in the Rutherford County Courthouse with wide gowns and fancy crinolines, parasols and frilly lace.

On Christmas Eve of 1862, a grand ball sponsored by the First Louisiana and the Sixth Kentucky regiments was held in the courthouse. Candles illuminated the large hallways, and behind each candle was a bayonet reflecting the light of the festive scene. A pyramidal chandelier of bayonets and candles hung from the ceiling, and trees of greenery and jars of flowers decorated the dance hall. Two B’s entwined in evergreen on the side of the wall represented the two Confederate Generals, Bragg and Breckenridge. Yankee flags captured by John Hunt Morgan were on display. With tunes of a musical blend of strings and brass, the revelers danced the stately cotillion and the graceful waltz far into the night, one soldier later recalled, “The candle light shone on fair ladies and brave men.”

The jubilance of a possible victory and the holiday spirits had taken an unpleasant turn on Dec. 31, 1862. The Army of Tennessee, under the command of General Bragg, and the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Union General Rosecrans, faced each other on the banks of the Stones River in one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. Once on the battlefield, Rosecrans deployed his army of 43,000 in position stretching from the Stones River at McFadden Ford to the banks of Overall Creek. General Bragg and his approximately 38,000 men were in close proximity, almost in a parallel position to Rosecrans’s Union Army.

How sad and disastrous! Only a few decades before all Americans were united, Red, White, and Blue through and through! Now we were tinged with gray. Our country found itself at war, painfully divided into two parts, aliens in the Republic, devoted patriots and ideological rivals driven asunder in a once-united America.

As the sun went down on the evening before the battle, Dec. 30, 1862, the sadness was elevated, prevailing over the wintry landscape. Perhaps, in that moment, all were once again united by the possibility that tomorrow there would be a violent struggle and death was imminent. On the edge of the open fields in the cedar glades were darkened camps with shadowy clusters of soldiers around amber firesides. The cold, damp air was filled with fear as depressed soldiers longed for home.

Cognizant of the bloody encounter that surely lay ahead, a peculiar circumstance occurred. Soldiers from both armies crossed the lines and began swapping tobacco and conversing around each other’s campfires. When one of the army bands struck up the tune “Home, Sweet Home,” the opposing band joined in and together they played the nostalgic melody. Obviously, this gesture was a diversion away from the terror ahead and the homesick loneliness. The music floated over the cedar thickets and pastureland, a dismal, surreal scene, for the next day that field would be littered the dead and the dying. The Battle of Stones River recorded the highest casualties of any major battle of the Civil War—12,906 Union soldiers and 11,739 Confederates with the total casualties reaching 24,645.

This story begs the questions “Why war?” “Where does it begin?” Perhaps, war originates in our minds—negative thought patterns, seemingly uncontrollable antagonism, resentment and hostility that erupts into the vehemence of war. Could it be that this progression occurs, our thoughts produce words, our words produce action, our actions produce the future? Perhaps, it is birthed in our spirits, a fierce, invisible force from the outside waging war relentlessly with our minds.

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.

If war begins in our negative mindsets (how we feel), then how can we change the way we think? Could it be that we feel the way we feel because we think the way we think? Possibly, the changing wrong thought patterns just might end war forever. The battle to change our minds begins as we realize how powerless we are to change anything, even our minds, without God’s help. However, without a doubt, we must take responsibility for changing our minds. We must do our part for change to happen. God will partner with us to make the necessary changes in our thought patterns when we quit making excuses and blaming others for our bad behavior.

God has made change possible as we choose to renew our minds—learning new ways of thinking. While winning the battle over negative thoughts, we gain control over one thing in life: our attitudes! If we change our attitudes, our thoughts will change. As the cacophony of confusing thoughts begin to bombard our minds, we can begin to take control of our negative mindsets, capturing them one thought at a time. It is never too late to begin again. Our past does not have to dictate our future.

Apparently, as we begin to change our mindsets more positively, we become aware that it takes a lot more energy to entertain destructive thought patterns than positive ones. While we get control of the war waging in our minds, love begins to transform us into vessels that can be used in a different way. “Out with the old and in with the new!” Victory is evident in our new lifestyles as we learn to think like God thinks, love like God does. The veil is lifted, and we begin to serve others rather than ourselves. Passionately, we proclaim the words in this old plantation gospel tune: ain’t gonna study war no more, ain’t gonna study war no more. . . study war no more!

“Oh! Susanna”

I love this version by John McEuen (Former Heritage Award Winner at Uncle Dave Macon Days), probably the best old-time banjo version:

“Home, Sweet Home”

This version by Deanna Durbin is probably the most historically accurate: