Professor Aaron Deter-Wolf will be teaching a course, The Anthropology of Tattooing, at MTSU this fall. The course is offered as an upper-level Topics in Anthropology class through the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, but when the course was taught for the first time in fall of 2012, a variety of students enrolled including visual arts, art history, biology, psychology and sociology majors.

The course syllabus states, “For thousands of years humans have been aware of the capacity of our skin to bear permanent markings, and cultures from Polynesia to the Arctic Circle have devised modifications through which to define, decorate, enhance, and sanctify their bodies. Tattooing—the process of inscribing the skin with permanent colors and symbols—appears across the globe and throughout human history.”

However, up until the last decade of the 20th century, Western society labeled tattooed individuals as “savages, criminals, deviants and freaks.” So there has been a lack of serious academic discussion about the practice of tattooing. The goal of the course is to use the tools of anthropology, archaeology and ethnography to explore this ancient practice, giving students a new perspective and allowing them “to independently evaluate the historic and modern role of tattooing in their own society as well as the portrayal of tattoos and the tattoo community in the world media.” Wolf explains. “There are a lot of myths, half-truths, and misunderstandings about tattooing on the Internet and in the media, and another goal for the class is to equip the students with the knowledge and ability to objectively assess the role of tattooing in modern, western society.”

He notes that while the media refers to tattoos as a “new fashion” that’s “no longer just for sailors,” Western society has a historical connection to tattooing dating back to the Bronze age that branches across all social classes.

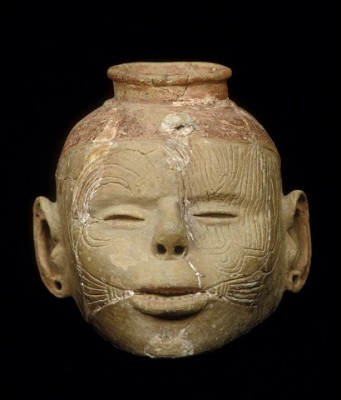

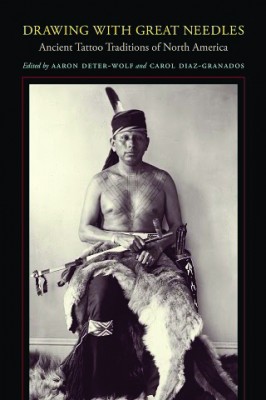

For the past decade, Wolf has been researching archaeological evidence of ancient tattooing with a focus on ancient Native American sites and artifacts from the Eastern United States. He is also involved in several museum exhibitions and conferences on the topic and has edited a volume on ancient Native American tattooing (2013, University of Texas Press), and also contributed several chapters to a volume on ancient tattoos and body modification through the University of Zurich that came out this past January. He is also a part of the curatorial team of “Tattoo: Ancient Myths, Modern Meaning,” a traveling exhibition about the art, history, and culture of tattoos that will launch in 2015. “I was brought on board to help identify artifacts and ancient art that might be included in the ‘History and Culture’ section of the exhibition.”

Wolf explained that most ancient cultures practiced some form of body art, most including the practice of tattooing, and there are preserved, tattooed human remains from all over the world. “Otzi is perhaps the most famous of these, though contrary to most reporting he is not the oldest tattooed body,” states Wolf, “That honor goes to a Chinchorro mummy from South America dated to about 6,000 BC.”

Until the past decade, there has been little effort to identify artifacts of tattooing found in archaeological studies outside of Oceania. “One of the main goals of archaeology is to understand the lives of people in the past, and the virtual absence of identified tattoo tools in the archaeological record represents is a major aspect of ancient life that we’ve been missing,” says Wolf. For example, we know ancient Egyptians practiced the art of tattooing, but of the millions of excavated artifacts collected from Egyptian sites over the last century, “fewer than five implements have been identified as possible tattoo tools.”

I asked Wolf if he had encountered any negativity or resistance to his work in the world of academia given the stereotypes that are still commonly bestowed upon tattooed individuals.

I asked Wolf if he had encountered any negativity or resistance to his work in the world of academia given the stereotypes that are still commonly bestowed upon tattooed individuals.

“So far my work has been well received by colleagues, and I haven’t encountered any outright negativity.” He adds that in 2009 he organized a “conference symposium on ancient and early historic Native American tattooing and body modification for the annual meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference.” He also participated in an ancient tattooing and body modification symposium held at the annual meetings of the European Association of Archaeologists in 2010 and 2011.

“So far as I know, these were the first academic colloquia ever devoted to ancient tattooing. They were all very well attended, and resulted in two volumes published this past winter (Drawing with Great Needles, which I edited, and Tattoos and Body Modifications in Antiquity).

Despite growing interest in the subject of ancient tattooing, the number of scholars seriously engaging in examinations of the field is still relatively small. Anna Felicity Friedman, lead curator for the traveling tattoo exhibition, noted that, “Unlike earlier scholars who have written on the subject, many of the new generation of tattoo scholars are ourselves a part of the tattoo community.” Wolf states, “I’d like to think this gives us insight and an understanding typically absent from earlier scholarly literature. I hope it also helps broadcast to the tattoo community that the work we’re doing is based on genuine interest and appreciation of the practice rather than outdated stereotypes or ivory-tower academia.”

Wolf explains how studying the ancient art of tattooing becomes a discussion about much more. He quotes anthropologist Alfred Gell, who wrote that tattoos in Polynesia “played such an integral part in the organization and functioning of major institutions (politics, warfare, religion, and so on) that the description of tattooing practices becomes, inevitably, a description of the wider institutional forms within which tattooing was embedded.” Wolf says he has found this to be true for all historic tattooing cultures. “When we discuss a region or group in class we’re talking not just about the tattoos, but also their archaeological past, social structure, art and iconography, political history, belief systems, and worldview.” He adds that when discussing contemporary tattoo culture in the MTSU course, “we do so in connection with classical history, cultural appropriation, the Age of Discovery, colonialism, genocide, world expositions and human zoos, historical tattooists, and the history and teachings of Christianity and Judaism, plus more.”

I also asked Wolf a lot about tattoo discrimination and if as the art of tattooing becomes more widely discussed in academia, will we eventually see ripple effects in our everyday lives such as less tattoo discrimination in the workplace? He replied that he did not expect to ever see tattooed individuals as a protected class in America, outside of those pertaining to religious practices, but he also cited an interesting 2008 study by MTSU Department of Psychology’s very own James C. Tate along with Britton L. Shelton, which “examined personality correlates for tattooing and body piercing.” Of 1,375 undergrad participants, 25 percent had at least one tattoo and about half had a piercing of some kind. “The authors concluded that there were no personality differences between body-modified and non-modified individuals, and suggested—rightly I feel—that their results indicate these forms of body modification have entered the mainstream.” Wolf believes that research has shown the general acceptance of tattoos among employers has improved just since the release of that study.

Wolf noted that he has noticed a more accepting attitude towards tattoos in larger urban areas more so than in suburban or rural settings, but that it still depends largely on specific demographics. “Acceptance of visible tattoos will obviously continue to grow in the future as the percentage of the tattooed public increases and as tattooed individuals rise through the employer hierarchy. However, I think it’s safe to say that it will be some years yet before we’ll regularly see visible tattoos in more conservative professions and workplaces.”