Boyhood, director Richard Linklater’s latest feature, follows in the footsteps of Linklater’s own Before . . . trilogy as well as Michael Apted’s Up series in its depiction of the same people/actors and how they change and grow over the course of many years. Whereas Apted’s documentaries serve mostly as a series of time capsules of individuals, Linklater is more concerned with using the real-life passage of time as an ally to his storytelling. Filmed from 2002 to 2013, Boyhood is the perfect distillation of this process; a whole childhood in a single film.

The movie begins with Mason Evans Jr. (Ellar Coltrane), a 5-year-old boy living in Texas with his older sister, Samantha (Linklater’s daughter, Lorelei), and their mother (Patricia Arquette). The time capsule is in full effect as Coldplay’s “Yellow” plays over the opening. There’s an effortlessness and naturalism to these young actors, especially the gregarious and deviously intelligent Samantha, picking on her younger brother only to play the victim when she gets caught. Watching as their mom juggles getting the kids ready for school, going back to school herself and the dating scene could be a movie in itself. The story is as much hers as it is Mason’s, her struggle to provide the best for her children expounded upon when a young Ethan Hawke—a fun-loving, care-free rocker dad not yet willing to give up his own childhood for the sake of his kids—arrives to pick them up for the weekend.

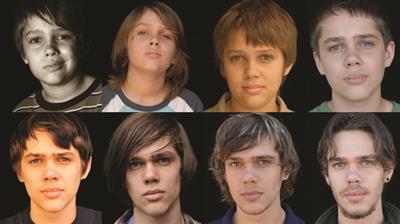

Linklater said his goal was to shoot a 10–15 minute short film every year and then edit it together as one. What sounds like a gimmick becomes Boyhood’s strongest asset; the resulting film is greater than the sum of its parts. We watch Mason and Samantha make friends and lose them, join families and leave them, and navigate the awkward teenage years. Their constant moving and acclimating to new schools and homes is made all the more poignant as they age in sped-up time before our eyes, and the novelty of watching the same people at different stages of their lives, rather than different actors or old-person make-up drawing attention to, rather than creating the illusion of passing time, makes for one of the most emotionally resonant coming-of-age films in recent memory.