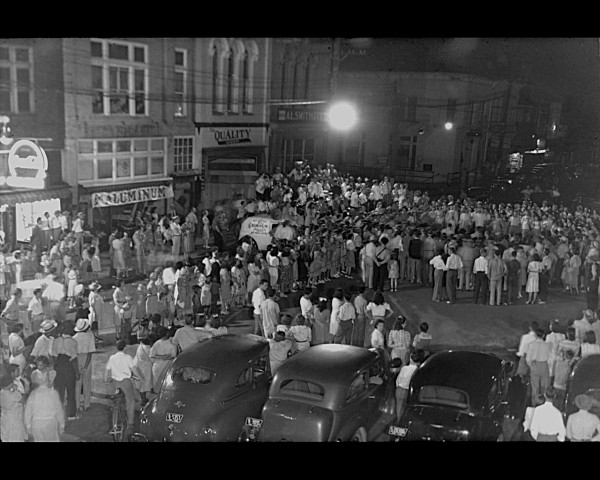

An image from Shacklett’s historic photo collection taken at the Murfreesboro Aluminum Street Dance in 1943.

Smooth, romantic tones swirled through the atmosphere, arming the cool of the evening. The young had come to dance and swing, but most had gathered at the Square to deposit their scraps of aluminum: pieces that had been crushed, cleaned and saved for the war effort. After all, salvaged aluminum was another way folks could make a personal contribution toward bringing victory nearer. Scrap metal could be used for grenades, binoculars and machine guns.

Mary clasped her Daddy’s hand tightly. Frustrated that she could not see what was going on in the center of the circle, she began to twist and turn to the music. When she was much younger and smaller, often her dad would hoist her over his shoulders in such situations. Although her dad had reluctantly brought his youngest to the street dance, he had firmly instructed that—if she insisted on coming—she’d better not get in the way. Being a policeman, he had to watch for crowd control. She could barely see the movement through the tightly gathered crowd. The compelling rhythmic sounds so energized the atmosphere that no longer could Mary resist asking, “Daddy, please, lift me up on your shoulders. I really want to see what’s going on.”

Mary’s family was one of the many of Rutherford County who remained on the “home front” providing citizen contributions during World War II. Her mother had purchased rationing books for food supplies, and her father had bought war bonds. Conservatively, Mom had saved ration stamps for weeks in order to get enough sugar to make her daughter’s birthday cake. They even had grown a “victory garden,” because Mary’s family wanted to do their part to “make food fight for freedom,” as a popular slogan of the day recommended. From far away across the ocean, a letter from Mary’s brother had been written with his impressions about the war.

“. . . and honestly, Mom, I never realized what food means in a war until we got into Italy. Little kids with swollen bellies and peaked pasty faces crowded around us like starved dogs . . . men and women cried out, ‘Bread, bread, bread!’ I only wish you and Dad could have seen these people when we came in with the food. When we pushed on, we left friends behind us. If everybody back home could just see this once, they’d grow a Victory Garden just like you are doing. Don’t let any food go to waste. Tell everyone to handle food as carefully as we handle our guns and tools. Mom, food saves lives. Food is a weapon! I’ve seen it happen firsthand.”

Mary’s father smiled and said, “You’re just too big for me to lift you up these days. How about we move closer to the front of the crowd so you can get a better look?” he suggested, trying to satisfy his fidgety daughter.

What a sight she saw! Under the amber glow of the street lights, the music playing over the huge loudspeaker was propelling the dancers madly in the center of the crowd. A growing swarm of enthusiastic onlookers gathered around the circle, laughing and clapping. For a brief moment, the flurry of sounds seduced the crowd into forgetting the great peril and sacrifices that the war had brought to their community.

When America declared war in December of 1941, the Swing Era was already in full bloom. American popular music of the 1940s offered a dreamy world, creating an atmosphere of conviviality and familiarity throughout the culture and actually making the horrors of WWII seem more endurable. More than any other media, it was the “Big Band” music of the day that ignited and drew together a truly communal spirit all across America. Its soaring, brass-produced riffs and driving rhythms combined with memorable tunes and lyrics that knit our hearts and longings for loved ones who struggled, sacrificed, and dreamed to be home again, so far away from every county, village, town, and city. In our community in 1943, many still recall a celebration that affirmed this very strength of fellowship and common purpose, known as the “Aluminum Street Dance.”

Oral tradition has it that this event was the first to be broadcast in Murfreesboro. This significant moment in our community’s history paved the way for the creation of a local radio station, WGNS, in 1947. In addition, the broadcast marked the first time a slice of American traditional folk music styles (string band music) merged with mainstream American swing band music. In 1943, all converged around the collection of aluminum at a street dance on the Public Square which was broadcast across the community.

There’s no doubt that the Great Depression of the 1930s changed people’s values and thus changed American society forever. Up until the 1930s, the idea of government using its resources for relief was limited. Our national policy was not concerned with issues of social welfare. Prompted by loss of hope and despair, the country plunged into deeper poverty. By the 1940s and the beginning of World War II, the country’s economic condition began to stabilize; however, the welfare policies of the New Deal under Roosevelt did little to bring the end of the Depression.

As many Americans became unified in the war effort, the population was mobilized through rationing and collection of raw materials. In recent years, it has become more apparent to historians that it was World War II, not the Depression, which brought fundamental change in the American economy. The war itself became a social crisis that cut people adrift from normal and ethical moorings, producing effects that are still felt. It ushered in the runaway consumerism of the post-Second World War. As the economy took off after the war, potential consumers took off with it, surrounding themselves with as many material objects as possible to offset the “Great Depression” mindset.

While the American society became more homogenized by the war, merging values and ideology ultimately influenced popular music all across the nation. Before the war, music was ranked and charted through the popularity of sheet music by the “hit parade” and published in Billboard magazine. After a two-year musicians’ union strike and recording ban (1942–1944) intended to prevent the new medium of recorded music from putting performing musicians out of work, live music on the radio airwaves was indeed replaced by records, which became big business as commercial radio stations sold airtime in order to subsidize playing them. The record industry was born and more and more Americans became consumers of music, defining a business archetype that is followed to this day (albeit one in the throes of transition).

Once again, the paradigm is shifting as the digital era is changing the music industry, with more artists creatively taking control of their art. With this revolution, will a form of music come forth to unite and comfort in our day? So much of today’s musical landscape seems littered only with sound-alike “musical styles” and so-called artists who don’t even write their own songs.

We can’t help but vividly recall and appreciate a much richer musical heritage of days gone by. Perhaps the conversion of the music industry in this digital era will impede the frenzied and fanatical exploitation that has been occurring in the music industry for decades. What if this mighty revolution in our midst changes music and finds its way to mainstream America once again?

Here, the Andrews Sisters perform “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” a wartime hit in the 1940s. It made it onto the nationally aired Your Hit Parade in 1941 and 1942.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qafnJ6mRbgk