Murfreesboro Central High in the 1950s

In the fall of 1963, I was a freshman at Murfreesboro Central High. For nearly a decade, there were some established traditions left by many a teen, one of which were the dances and activities of “Tiger Den.” Tiger Den was a teen hangout found in two different locations at Central, one in the Old Tennessee College for Women and the other in a large room in the annex built in 1959. Teens gathered after football games as well as for casual get-togethers, mostly coming alone or as part of a group of singles.

I was a child of the ’50s, America’s final days of innocence and naiveté. According to today’s regulations, many of my friends and family, including myself, should not have survived this time failing to drink from childproof bottles, riding my bike without a helmet, drinking strange sugary slurps from waxed containers, riding in car seats that hung from the back support of the front seat, and playing all day without supervision until it was too dark. But I did survive, and, at 13, I found myself at Tiger Den after a Central High football game, sequestered on the girls side of the room—with my friends, of course.

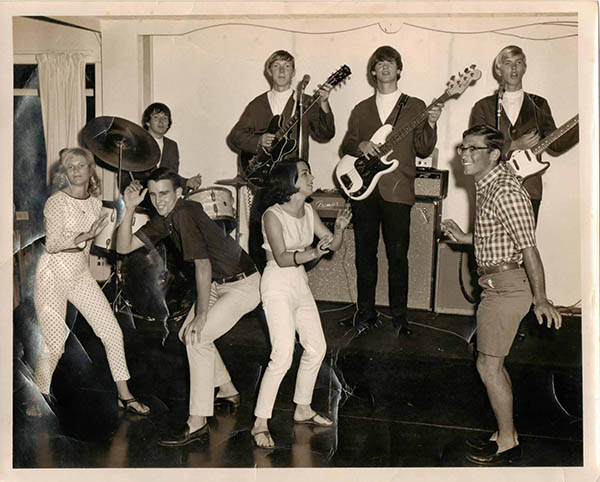

Coming from a turntable playing 45s at the back of a dimly lit room, was wild, loud and infectious music. As a child of the ’50s, watching American Bandstand every weekday afternoon for years, I had been fully educated and indoctrinated about these sorts of things. I had seen older teenagers dance (the Stroll, Twist, Mashed Potato and the Jerk) and wanted to imitate everything they did. Or at least I thought that I did, until I found myself a freshman in Tiger Den, a room filled with teen friends.

In 1963, the “Den,” as it was called, had been a tradition at Central for 11 years. According to Central’s newspaper, The Highlights, Tiger Den was formally opened Oct. 23, 1953, at Central on Main, which had opened in 1951 (after the old Central on Maple burned in 1944). With contributions from several civic clubs in town and support of $500 from Murfreesboro’s City Council, a gathering place for the town’s young people was created. By following the music of the ten-year period from 1953 to 1963, and the teens who attended Tiger Den, one can chronologically follow the story that took place all across America. In addition, this gives us clues about Murfreesboro’s favorite musical styles during that era.

By the early 1950s, popular music belonged to the realm of the white middle class and wholesome, clean-cut white performers. For a culture that was recovering from the atrocities of World War II and the emergence of the middle class in suburbs all across America, music was designed to be as innocent and inoffensive as possible. For the most part, the music of that era reflected one of the most peaceful times in America’s history.

The population of Murfreesboro had heard music of varied styles over the airwaves on WSM 650AM. Most of the primarily rural community listened to the Grand Ole Opry’s hoedown music. Then, on Dec. 31, 1946, as the new year of 1947 drew near, approximately 8,000 persons tuned into their first local radio station. It was a big thing for the county to get its own radio station. At 10 o’clock p.m. the static suddenly vanished and a strong new signal appeared. WGNS rang in the New Year of 1947. As a song from the mid-1930’s (but still popular in the late ’40s) jovially explained, “The music goes round and round and it comes out here.”

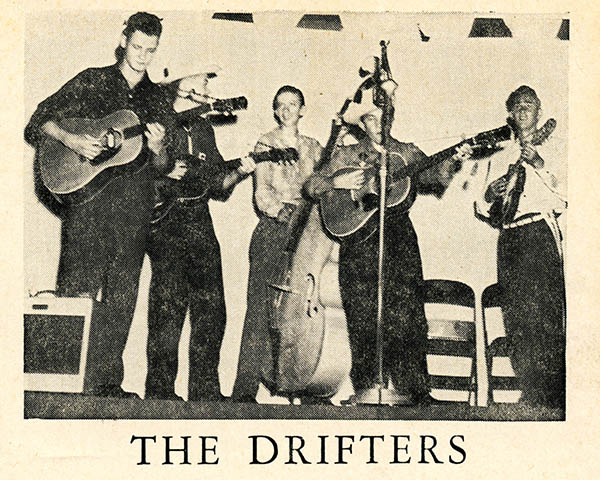

According to the Central Highlights newspaper, during the Tiger Den’s first year a group of five boys got together and began playing some of the craziest music ever heard at Central High. This was the Central High String Band! The players were Billy Spence, Billy Henson, Kenneth Bean, Floyd Leonard and Roy Melton. Even at their young ages, all had been professional musicians in the area. They played square dances at Tiger Den during 1953 and ’54. In the 1950s, a student Tiger Den steering committee was involved in the planning and implementation. The Key Club installed a counter and several tables for a snack bar. What fun it was to play the piano and dance, join in a card games or a game of pool on the donated billiard table. Many would bring 45 rpm records from home. Sounds of Les Paul and Mary Ford, Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee and even our homegrown Tennessee girl, Dinah Shore, were all favorites.

This is validated in the school’s newspaper, Central Highlights, dated Feb. 2, 1954:

One day I wandered over to Tiger Den and found a lot of boys playing pool and some girls playing ping pong and many more games. I think that place is wonderful! Everybody seems to like it. About sixth period, the other day, I dropped by the den and there was Sandy Weisburg teaching a bunch of girls the can-can.

It was in the early days of the 1950s that musical styles began to merge creatively. Rhythm & blues pioneers began to exert a primary influence in all of America’s music. Records waxing some of the first indications of the rock ’n’ roll sounds soon to follow somehow fused shouting, African American gospel with up-tempo jump blues and elements of pop and country to create a completely new, still-unnamed genre of music. These new recordings, showing up on jukeboxes and in teen hangouts like Tiger Den, began to influence America’s teens in a way that was unacceptable to the post-World War II generation.

These musical innovators embellished their sound with multiple horns and intense, shouted vocals. The sound, earmarked by driving rhythm and the honking of the tenor sax, was the precursor to rock ’n’ roll. With their gospel-informed delivery, vocalists began to identify sounds heretofore kept behind the racial barrier, eventually resulting in wide-ranging vocal styles like those of B.B. King, Little Richard and James Brown.

All the fears and myths related to the supposedly more active sexuality of blacks and the integration of the races were having a powerful effect on the sentiment of the day. In the minds of conservative, older whites, rock ’n’ roll was going to destroy everything that was American. In its humble beginnings, rock was hated by the general Caucasian public and considered to be the devil’s music. One newspaper headline read, “Rock ’n’ roll is a communicable disease. Rock ’n’ roll has got to go!” The division even caused riots and banning of the music across America.

In order for rock to rise to mainstream success, what was needed was the reversal of this effect—namely, what Memphis entrepreneur Sam Phillips described as “a white boy who sings like a black man”—to make the sound more palatable and presumably less anxiety-provoking for whites. That would be Elvis Presley, who visited Murfreesboro in the early 1950s on local radio station WMTS, thanks to owner Tom Perryman. Elvis went on to become the King and reigning icon of rock ’n’ roll.

On WGNS, every afternoon around 4 until sign-off at 10 p.m. in the 1950s and ’60s, the new sounds of rock ’n’ roll could be heard across the county, exposing every teen to the latest hits of the day. Locally, teens had an eclectic musical experience from the airwaves of their Good Neighbor Station, WGNS. In the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s Carl Tipton and the Mid-State Playboys did a “live” radio show from a different local business every day at noon.

After 1964 and throughout the late 1960s, the innocence of the Tiger Den experience began to lose its appeal for teens in our community as our country and music began to change dramatically. The events of the 1960s—the assassination of our president, John F. Kennedy, his brother Robert and Martin Luther King Jr., along with race riots and the tension over Vietnam—transformed America’s music forever.

Here’s the final twist to this story. In my senior year in 1967, planning the senior prom at Tiger Den, an emerging group at the time called “The Allman Joys” appeared in the area. As I remember (though as yet unconfirmed), this group played for our senior prom at Tiger Den. I did ask the famous songwriter, record promoter and producer John D. Loudermilk to confirm this possibility. During this time, Loudermilk confirmed that he was booking the group at functions all across Middle Tennessee in the Nashville area. The group would later become one of the most famous of the 1970s, The Allman Brothers Band. He commented, “I just sent them to California. They just didn’t catch on here!”

From the 1950s to the 1960s, the teens who attended Tiger Den, like others all across the USA, participated in shared cultural experiences that defined and transformed the youth landscape and, ultimately, America itself—not necessarily for the better.

Some say that, over the past 50 years, our culture has fallen into an abyss. One result of such a descent could be the powerful and dark forms of creative expression found in many recordings of our day. Sadness and cynicism have found a place in our consciousness, reflecting our affinity with the ever-present emptiness within us. In the 21st century, we have affirmed the notion that mankind alone has all the answers. The emerging belief from the last century tells us that “God is dead, therefore man becomes God and everything is possible. There really is no truth!”

There is an Eternal Truth that can transform us from the darkness into Light. We have an even more powerful force: God’s love. He never wanted us to taste evil. His plan has always been for our good. Clearly, as God’s love frees us from evil’s soul-destroying spirit, this Eternal Truth can penetrate deeply into every fiber of our society, including all creative expression.

Great songs for Dancing at Tiger Den from 1953–64: