During the 19th century, the American population was living in a predominantly rural society, in a manner far more dispersed and remote. Whether their lives were filled with 12-hour days on farms, or activities in the expanding cities, entertainment was a part of their daily lives. The range was wide, from banjo pickin’ on the front porches and barn dances to staged, formal, self-structured entertainment. But whatever its form, entertainment, as in any other culture across the decades, has always fulfilled an inner desire to break symbolic conventions. In a search for release, we are driven to desire diversion from burdens and responsibilities—the consequences of the pain and suffering of a society overwhelmed by toil.

In addition to satisfying social and emotional needs, entertainment provides a secondary function, a carrier of ideas and attitudes. Many times, in the name of entertainment, people simply create parodies of those whom they misunderstand. Such were the days and times in 19th-century America, when minstrelsy became the most important form of mass entertainment. Minstrelsly, which caricatured blacks, tragically demonstrates the relationship between black and white Americans during the 19th century, underscoring the notion that humans have a propensity for making fun of what is not understood!

As a quote by historian Alexander Saxton emphasizes, “It was the black American who became the dominant character in American humor through white entertainers impersonating blacks that toured every city, town, and village from the 1830s to the First World War.”

The appeal of minstrelsy lay not only in the legitimately entertaining music, rhythm and catchy phraseology of black folk and religious songs, but to distort the image of the black American as a delightfully ignorant and nonthreatening buffoon. In the pursuit of his craft, the white entertainer collected, imitated and conveyed unflattering racial stereotypes to a largely white audience, the effects of which may continue subliminally in American dogma today.

In the 19th century, as it is in the present day, the popular entertainer was a powerful figure, reflecting and having the ability to shape public opinion.

During this time, writer and political commentator Walter Lippmann wrote, “The subtlest and most pervasive of all influences are those which create and maintain the repertory of stereotypes. We are told about the world even before we see it. We imagine most things before we experience them.”

The prevailing impact of the entertainer on American society can be traced to this moment in our history. This influence demands our reflection and study as we begin to understand our compulsive obsession to be an “American Idol” in the 21st century.

In the early days of minstrelsy, the practice of blackface served as a racial marker, suggesting that the performer would be portraying aspects of African-American culture. A closer look through more enlightened eyes, though, reveals that the identifying trait of minstrelsy is its blatant racism. However, the blackened face also served as a type of mask to shield the performers from identification with their roles. The minstrels borrowed from and parodied European musical styles. Most entertainers all traveled together in the same circuits as circuses, opera companies, and other virtuosi, blending musical and performing styles, cross-pollinating them all across America. These parodies were detrimental, creating contradictory beliefs about class, race and gender. In addition, the performances marginalized women, defining their domestic roles in narrow terms typical of the era.

On the positive side, minstrelsy developed into a commercially viable entertainment form from the combination of seemingly opposing genres. These continued to influence and shape American entertainment well into the 20th century. Marking and defining the advent of American popular music, many of these songsters were given an opportunity to work as the business of entertainment evolved. Nevertheless, the stereotype died hard in America, with descendants of blackface performers becoming popular in vaudeville and later in film. They made their way into movies, radio shows and early television programs such as Amos ’n’ Andy and stage appearances of popular entertainer Al Jolson’s blackface character in The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length movie to use a synchronized soundtrack (signaling the impending demise of silent movies).

“Oh! Susanna,” “Dixie,” “The Camptown Races,” “Buffalo Gals” and “Jimmy Crack Corn” were all popular songs of the early minstrel era. Songs such as these provided the musical source for today’s bluegrass, country, old-time, and Americana music. The musical technique was a combination of styles from Celtic and African-American music. Joel Sweeney, the earliest known American banjo player as well as a practitioner of minstrelsy, made the instrument very popular in the 1830s. (In so doing, he helped to obscure the fact that the instrument has its origins in Africa.) In 1843, the very first minstrel show was performed with a banjo, fiddle, bones and tambourine. From that point, “minstrel mania” swept the nation. Hundreds of troupes began performing, giving birth to multiple genres of today’s musical styles.

American vaudeville grew out of the culture of incorporation that defined American life after the Civil War. The development of vaudeville marked the beginning of popular entertainment as big business, dependent on the organizational efforts of a growing number of white-collar workers and the increased leisure time, spending power and changing tastes of an urban, middle-class audience. Business-savvy showmen utilized improved transportation and communication technologies, creating and controlling vast networks of theater circuits that standardized, professionalized and institutionalized American popular entertainment.

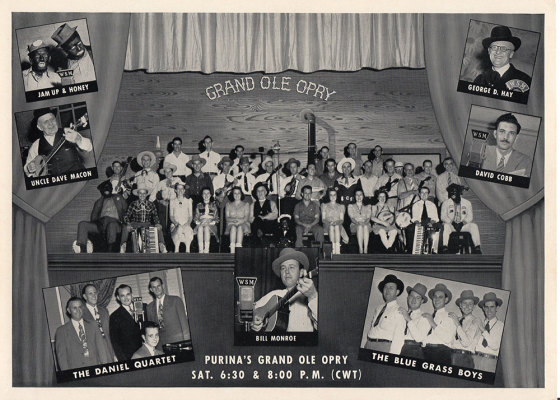

The banjo, the foundation of the minstrel show, was always played with a fingernail in the stroke. The simplified version is called “frailing” or “clawhammer.” One of the most popular vaudeville acts in the South was Uncle Dave Macon with his clawhammer style of banjo playing. Macon popularized his zany, eccentric performing style in the early 20th century. It seems that such legends are born nonconformists. Such was Uncle Dave Macon. Capturing many of the early minstrelsy styles of the 19th century and bringing them to vaudeville in his clawhammer style, Uncle Dave Macon, “King of the Hillbillies,” helped bring the banjo into modern times.

Uncle Dave Macon, the Grand Ole Opry’s first superstar, was born in Smart Station near McMinnville, Tennessee. When Macon was a teenager, his parents owned a hotel in Nashville. The hotel catered to many vaudeville, minstrel and circus performers who stayed in the hotel. By his middle teens, when he bought his first banjo, he had grown to love the music and performing traditions of the previous century.

Long before he was exposed to the vaudeville traditions, Macon had absorbed another powerful tradition: rural black folk music. Uncle Dave once said about his influences, “I was born on a Warren County farm and I learned the tunes of the darkies.”

Uncle Dave’s sizable repertoire consisted of many fragments of tunes from whites and blacks. Uncle Dave’s music really is a case study of traditional 19th-century music and entertainment. As with many of his pieces, the “core” of the song which he acknowledged was borrowed from black traditions. One song, for example, was one he mixed up and recomposed to suit himself. Called “Rock about My Saro Jane,” it was originally an African-American work song sung on 19th-century steamboats as “Saro Jane.”

Before the early 1920s and the birth of the Grand Ole Opry, the flamboyant Macon had enjoyed popularity as a professional entertainer in the Lowe’s vaudeville circuit. Then it happened: The old-time craze was sweeping the nation and Uncle Dave Macon, with his wealth of experience from vaudeville and burlesque, was at the right place at the right time. His wild, showy comedic style of entertainment was something to behold. In those early days of the Opry, Uncle Dave has come to symbolize the spirit of the day. Uncle Dave, as an established entertainer on the circuit, was needed by the Opry more than he needed it. He had made more than 30 recordings and had toured thousands of miles across the mid-South before he first sat in front of a WSM microphone.

Uncle Dave had become extraordinarily popular by word of mouth through his stage appearances and records most, of which were recorded in New York City. Early string band artists such as Kirk and Sam McGee, and fiddlers Mazy Todd and Fiddlin’ Sid Harkreader, would tour around the South with an old-fashioned “word of mouth” advertising approach. They would go into a town and put on a sample show, and let the grapevine do the rest. In a raucous frenzy, Macon and his musical magicians created one of the most dynamic string bands ever, sending hundreds in the audience to their feet, dancing and stomping to the jug-band sounds of Macon and his Fruit Jar Drinkers.

Uncle Dave proudly played from town to town, his instrument case denoting his notoriety. Sam McGee, who had once played guitar with Uncle Dave, recalled, “I will never forget what Uncle Dave had on his instrument case—‘Uncle Dave Macon, the World’s Greatest Banjo Player.’”

Macon’s musical magic continued until his death on March 22, 1952.

The musical heritage is celebrated every year at Uncle Dave Macon Days at Cannonsburgh Village in Murfreesboro. The 38rd annual celebration starts July 10 with the Matilda Macon Folk Arts Village, Dave Macon Artisan’s Court and Marketplace and the old-time musical and dance competitions. Capturing the minstrelsy spirit and flamboyant antics of Uncle Dave as well as a tribute to Lester Armistead, founder of the Tennessee Mafia Jug Band, is the return of the jug band competition on Friday evening, a “don’t-miss” event.

New this year are three featured sunset concerts, the first of which will commence at 7:00 p.m. on Friday, July 10 with Russell Moore and III Tyme Out followed by 2015 Heritage Award Winner Dr. Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys. The festival continues July 11 with the famed motorless parade down Historic East Main to Cannonsburgh at 10 a.m. and the national old-time dance and banjo competitions. On Saturday evening at 7 p.m., the sunset concert series will feature the Hog Slop String Band and the presentation of the 2015 Trail Blazer Award Winners, The Steeldrivers. At noon on July 12, the festival brings the gospel showcase, antique car show and community service fair. The festival concludes with Kristina Craig and Exit 148 and the final sunset concert, featuring Larry Cordle and Lonesome Standard Time.

The festival honors the man who popularized America’s “roots” music. For more information about the 2015 Uncle Dave Macon Days Festival, visit uncledavemacondays.com, e-mail sponsorudm@gmail.com or search Uncle Dave Macon Days on Facebook.