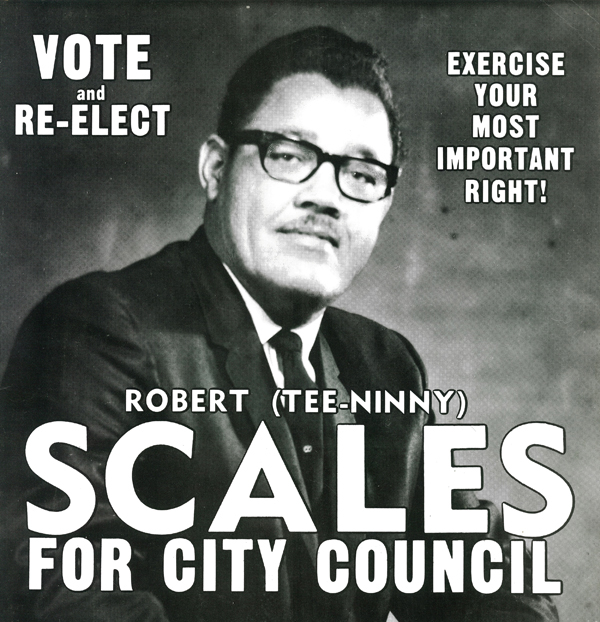

How do you tell a story about a historic figure that you never met? If you just read and repeat the stories already written, then you really have not brought forth any new insight or information. If you go to those who have met or who knew that person professionally, you can get an idea of the public face of the person, but that still doesn’t give you any real insight into the person. And, as is true with any story ever told, not everyone remembers it the same way. But now, I submit to you that with the following story of Robert (Tee-Niny) Scales, I have stumbled onto the best way to tell anyone’s story: through the eyes of a loving daughter.

Madelyn Scales Harris is the daughter of Mr. Robert and Mrs. Mary Caruthers Scales and is, in her own right, an accomplished and distinguished representative of the city of Murfreesboro as well as a second-term councilperson, a third-generation business owner and a voice for the people she represents.

Madelyn Scales Harris

Talking with Madelyn about politics, she is serious, often frustrated and occasionally unsure that she has done enough to help city workers and the people of Murfreesboro, but she vows to keep trying. The sincerity and conviction she carries in her words leave you no choice but to believe her. It will also give you the feeling that it is as much a learned behavior as a self-taught conviction. You can feel in her demeanor that she grew up in an environment that provided her a sense of community and helping others. Talk to Madelyn about her father and her demeanor changes almost instantly, to that of a reminiscent, proud and loyal daughter that has great memories of her family. Although more than once during our conversation, those memories seemed touched by a melancholy for days gone by. As much as one can admire, I do admire the politically charged version of Ms. Scales Harris, but I much more enjoyed the daughter speaking of her late father and family.

Robert Winston Scales was born to Henry Preston and Willie Burkeen Scales on June 22, 1926, and died Oct. 30, 2000. He was a civic leader, politician and small business owner in Murfreesboro, Tenn. When his oldest sister, Ruby Mae Thompson, saw him for the first time, she said, “Oh, look at my tee-niny brother.” Her attempt to say tiny became a lifelong nickname for Robert. That nickname became as recognizable as his first or last name. Throughout the years of his life and even up to today, the name “Tee-Niny” or “T-90” is still used to refer to him. In 1949, Robert married Mary Caruthers Scales (Sept. 24, 1928–Oct. 6, 2013). She would become a teacher at Bradley Elementary, the first black faculty member at Middle Tennessee State University, the first black teacher at Bellwood Elementary and later the first African American woman elected to the City School Board and City Council in Murfreesboro. Robert and Mary had six children: Robert Winston Scales Jr., Melvin Pearson Scales, Preston Marcellus Scales, Madelyn Scales Harris, Joan Scales Simmons and Sandra Renee Scales.

“Dad followed in the footsteps of his father, and was the second-generation owner of Scales & Sons Funeral Home,” Madelyn explained. He took over the business at the youthful age of 20, after his father passed away. With a smile that showed her pride, Madelyn said, “Just like his father, Dad was a people person. Mr. Preston started Scales & Sons Funeral Home in 1916. After the passing of Preston Scales, Dad took over and ran the funeral home until the time of his death.”

Today, the funeral home is run by Madelyn and family members. Scales & Sons is the oldest black-owned funeral home in Murfreesboro and possibly the oldest of all the local funeral homes. Madelyn explained the community spirit of her family business that went back to her grandfather.

“Mr. Preston had a program called the Helping Hand Burial Program,” Madelyn said. “I was once told about a person that had passed away and the family did not have any money for the burial. Grandfather said to them, ‘I’m not asking for anything but the burial clothes. Don’t need to see you again til the funeral.’ My grandfather would bury people for chickens if they could not afford a funeral. Everyone knew Mr. Preston as a people person. My father was very much like him.”

“Mr. Preston had a program called the Helping Hand Burial Program,” Madelyn said. “I was once told about a person that had passed away and the family did not have any money for the burial. Grandfather said to them, ‘I’m not asking for anything but the burial clothes. Don’t need to see you again til the funeral.’ My grandfather would bury people for chickens if they could not afford a funeral. Everyone knew Mr. Preston as a people person. My father was very much like him.”

Robert Scales made history in April 1964, when he became the first African American to win election to the city council and one of the first, if not the first, elected black officials in the South. Not only did he win an election in 1964, he carried the ticket, meaning he got more votes than any other candidate. As of the 2010 census, there were 108,755 people residing in the city. The black community makes up only 15 percent of our population today; it was much smaller in 1964. So, although there are still many who will testify to it, the math alone proves Mr. Scales was very popular among white voters as well.

“He won because everybody knew him and respected him, and that went all the way back to his father,” Madelyn said. “That says a lot for the unity of our town, but that does not mean that there wasn’t racism and bigotry . . . The night dad won the election, we started getting threatening phone calls, bricks were thrown through our windows and we found a cross burning in the yard. A guy named Jack Winset, who owned Jack’s Glass, was replacing windows every week in our house. One day, he knocked on the door and said to T-90, ‘I am embarrassed about this. Once a week we will come by and replace your windows for free.’

“After Dad won, he told my mom, ‘In the next four years I’m gonna make sure that every department in this city has an African American in it,’” Madelyn continued. “Mom said, ‘That’s gonna be a big job.’ Dad said, ‘I can do it. I want equality for this city. Not just for black people, everyone.’ At the end of his first term, there was a black person in every department.”

Madelyn went on to describe an encounter in the 1960s.

“During the days of the race riots, someone from Nashville called my dad and told him there was a bus[load] of protesters coming down to Murfreesboro. Dad took me with him to meet that bus, over the objection of my mother. We waited in the area of where Sloan’s Cycle is today—back in those days it was all woods. When Dad saw lights coming, he got out, told me to stay in the car. Dad stopped the bus and told the protesters that we don’t riot here, we reason things out. Because of my father, they turned the bus around and left,” Madelyn said.

Madelyn relayed another story to show the character of her father: “When I was a little girl, I was out playing one day and a white man, walking by, spit in my face. Dad took me in the bathroom and wiped it off. Dad was mad and crying, Mom was trying to calm him down. I asked Dad, ‘Are you going to go after him?’ He never answered me. Years after that, we were watching a ball game on TV one day and he turned and said to me, ‘Do you remember the day that man spit on you?’ I said, ‘Oh, gosh, Daddy, I stayed mad at you for so long.’ He said, ‘Now that you are old enough, let me explain why I didn’t go after him. Back then, if I had gone after that guy, I wouldn’t have lived to see you grow up, see you go to college, get married or see my grandkids. If I had gone after him, I would have spent the rest of my life in prison. So I had to decide, do I live to see my children grow up or get revenge? I chose my children.’ Over the years, race relations improved and Dad was a huge part of that. ‘Come, let us reason together’ was a saying and Robert Scales campaign slogan. When issues arose, he would tell the council, ‘If I can’t get the whole loaf of bread, I will settle for half. Let’s talk about it.’

“My dad used to put money in people’s hands when he shook hands with them. I asked him why, and he said ‘We serve God when we help people.’ He told us kids on his deathbed, ‘I’m not leaving you with a bunch of money, but I’m leaving you with a good name.’ Everything Dad had, he gave away,” Madelyn said.

Then a large smile came across Madelyn’s face, “I remember my dad walking into the house one afternoon, with a T-shirt, trousers and socks. Dad always dressed sharp, and when he left earlier that day he had a suit on. Momma asked him, ‘Tee-Niny, where are your clothes and your shoes?’ He said, ‘Mary, it’s this new preacher in town, he’s over at the Key Chapel. His car was stopped and I asked if I could help him.’ During the conversation, the preacher remarked that he liked his shoes and suit, so he gave them to him. Mom said, ‘Wait a minute, Tee-niny, where’s the car?’ Dad said, ‘I gave it to him and told him to return it when he got his fixed. If you don’t get it fixed, don’t worry about it, keep it.’ Mom just shook her head, held up her hands and said to me, ‘I’m used to it.’”

Even after his election to the City Council, there was still racism to deal with. Madelyn spoke of a council business trip to New Orleans.

“At dinner that evening, all the council members sat at one table except Mom and Dad, they sat them by the door. When the other council members were leaving, Joe B. Jackson asked my father if he liked the food and Dad said, “We haven’t even had a glass of water served to us.” They were all booked at the same hotel and after the other council members went to bed, Dad discovered that there was not a key for them. Dad asked at the desk and was told he would have to wait on the supervisor. After more than an hour passed in a very cold lobby, Dad told the desk worker,‘My wife is cold and we need a room.’ Before he could get the key, Mayor Jackson had to come down and identify him. When he was given a key, it was a key to the laundry room. Dad said, ‘At least it was warm.’”

Whatever your opinion of civil rights, it is undeniable that Robert Scales had a large crossover appeal. He spent 24 years (or 6 terms) as a council member, 16 of those years as the first African American vice mayor. In most of his elections, he got more votes than any other candidate, often more than all candidates combined. He began this at a time when race relations in the South could not be more strained. This was the same era of civil rights marches, segregation, sit-ins, physical confrontation with police and the Selma bombing.

“Dad knew people were looking to him for guidance and he had a huge backing from the white community. Despite any of his experiences, Dad never talked against a race. He was an excellent example of a leader and a peacemaker,” Madelyn said.

Stress plays a big part in any politician’s life, and Robert Scales was no exception. With a furrowed brow and a noticeable change in the sound of her voice, Madelyn said, “Dad came home stressed out after a council meeting in April 1988, where the council had voted against recognizing a holiday for Martin Luther King. Dad was so upset and stressed out about that. He had a heart attack that evening, and it ended his political career.”

Mary Scales

Although Robert Scales’ political career was over, the family name and dedication was still represented when Mary Scales finished out his last term and was then elected to another term. During and after his political career, Scales stayed involved in the community.

When Robert Winston Scales died on Oct. 30, 2000, it was quoted on WGNS radio, “The whole town stopped.” Flags all over town and at the state capital were at half-mast. During the funeral procession, every intersection and street had a police car or fire engine present, with the occupants paying their respects.

A State Proclamation honoring Mr. Scales was passed in 2001:

“We honor the memory of Robert Winston “Tee-Niny” Scales, reflecting fondly upon his impeccable character and his stalwart commitment to living the examined life with courage and conviction. The altruistic activities to which he devoted his time and energy: the American Red Cross, the Tennessee Municipal League’s Safety Commission and the League’s Human Resource Development Committee’s Board of Directors, the City Parks and Recreation Commission, the Tennessee Higher Education Commission, the Rotary Club, the United Way’s Board of Directors, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and many more,” the proclamation read.

Robert Scales was honored by the American Business Women’s Association as an “Outstanding Citizen,” by President Jimmy Carter as an “Outstanding Citizen of his Community” and as a “Murfreesboro Legend” by the Murfreesboro Chamber of Commerce.

“My parents sacrificed a great deal of their lives to make this a better city. Even with six kids and a business to run, they still wanted to help the community,” Madelyn said. “I wish Dad could have lived to see a school with the family name.”

In 2010, Madelyn Scales Harris ran successfully and has since been re-elected to the city council. Much like her father, she champions the citizens and city workers of Murfreesboro. But, affirms Madelyn, it wasn’t an easy decision to run.

“I was not going to run . . . God changed my mind. If God has some plan for you, he will slow-walk you down. Mom said, ‘You should run because are a good mix of your father and I.’ I said, ‘What if I don’t win?’ She said, ‘You won’t be the first.’ God made it clear to me, but I never asked God to let me win. Mom said, ‘If you win, get busy helping people.’”

Preston Scales, Robert Scales, Mary Scales and Madelyn Scales Harris have carried on a tradition of service to this town that spans more than 100 years. Robert Scales tore down a color barrier that even to this day still exists in other places. He was respected on a local, state and federal level. Mary Scales was the first black teacher at Bellwood School and Madelyn was its first black student. Today, Madelyn carries on the traditions forged by her parents. I watched as she proudly shuffled through pictures, newspaper clippings, awards and commendations that were bestowed on her father and mother, never saying a word about her own accomplishments. It is my hope that she keeps hers in separate box for when they write about her.

Lastly, I wish to add my own take on the impact of the Scales family. I grew up in this community and I saw racism firsthand; not just confined to black and white, but across all ethnic and religious boundaries. But, it wasn’t something that consumed daily life or created lasting problems, like it did and still does in so many other places. I submit to you that, although racism was and still is here, it’s not as bad here as it was elsewhere. When I was a child, I went to school, movies and played in the same playgrounds with black children and it wasn’t unusual to do so. At 49 years old, I have no personal recollection of segregated schools, white-only diners and black-only drinking fountains. Yes, they existed here, but they were not part of my life. By the mid 1980s, when I was in high school, there was a melting pot of humanity in this town comprised of almost every ethnic group you can think of. That kind of diversity is good for growth and the economy of our little slice of God’s country. It is my earnest belief that Tee-Niny and the Scales family played a huge role in the relative harmony of race relations in this town and making this the prosperous, diverse place to live it is today.