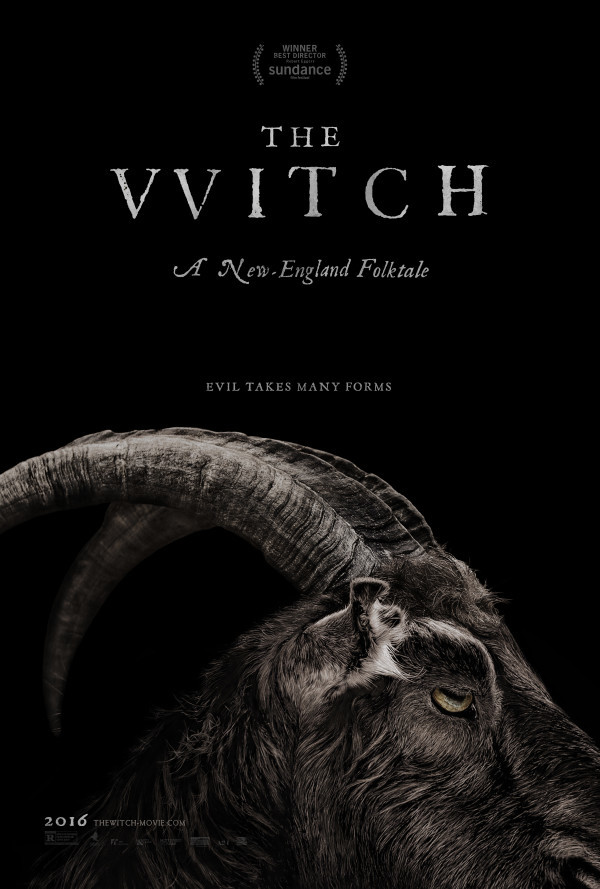

Witch-themed movies such as The Blair Witch Project and Rob Zombie’s The Lords of Salem often cast witchcraft in a contemporary setting, but first-time director Robert Egger’s Sundance-winning horror The Witch forgoes modern comforts and thrusts the genre back to its New England roots.

In fact, some might say it’s not even a horror movie. At least, not a typical one. It follows a trend of artistic fright flicks that focus less on gore and jump scares and instead on filling the audience with dread and anticipation. Those who enjoyed Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook can rejoice in the fact that The Witch delivers a similarly terrifying experience through ominous shadows, muted conversations and a relentless score—and sometimes, piercing silence—that keeps the tension palpable.

The film opens with a family’s patriarch, William (Ralph Ineson), on trial for unknown actions unbecoming of his Puritan faith. As both parties claim their actions are just, and William assures that his prosecutors are the ones erroneous in their faith, the council decides to banish William, his wife Katherine (Kate Dickie) and their four children. The family gathers their paltry belongings and are displaced to the unforgiving wilderness to exist on a modest settlement amongst the foreboding woods that threaten to engulf them. After settling their new home, Katherine gives birth to their fifth child, Samuel.

While many horror films use religion as a tired segue into an overused exorcism, The Witch bucks this pattern. Religious to its core, it succeeds tremendously without employing any one-prayer solutions or cheap, upside-down cross gimmicks. The household prays for answers to their plights, but they do it, well, religiously. The themes of sin and godliness permeate the film in its entirety, and each member of the family—except the newborn—has vices to overcome. As accusations of witchcraft, lying, disobedience and theft are thrown around, it’s hurriedly apparent that the members of this family don’t wholly trust one another. The titular witch who plagues the isolated family only snowballs these issues by testing their familial and religious resolve.

Speaking of that spell-casting, baby-sacrificing satanic witch, her screen appearances are few and far between. That’s not to say her presence isn’t felt; Egger made sure the witch’s influence extended far beyond her bodily form to the point that the witch and the sinister forest melded into one baleful fusion. “We will conquer this wilderness,” William assures his son early on, even before the witch’s presence was confirmed, suggesting that the wilderness was a breathing, living entity itself that bode just as much ill will as the witch. Much like Freddy Krueger poisons the dream world, the witch thoroughly infests the woods with her malevolence.

Obscure shots of the witch are all Egger grants to deliver a persisting fear of the unfamiliar. A cloak-covered, slumping figure, a naked, wrinkled, blood-drinking hag and a youthful succubus are just a few ways the witch is rendered. Her true face is only shown for a brief scene, but the truly haunting part is her features aren’t exaggerated to the point of diluting the revulsion. There’s no comical moles, no oversized noses and no sickly green skin common in witch interpretations. Too many horror films are spoiled by an embarrassingly exaggerated unveiling of the monster—think back to Insidious’ laughable demon, who looked more like a Bernie Sanders/Darth Maul hybrid than an otherworldly fiend. Viewers will long to alleviate the fright by writing off the witch as something grotesque and impossible, but Egger portrays her as just human enough to deny that comfort.

Obscure shots of the witch are all Egger grants to deliver a persisting fear of the unfamiliar. A cloak-covered, slumping figure, a naked, wrinkled, blood-drinking hag and a youthful succubus are just a few ways the witch is rendered. Her true face is only shown for a brief scene, but the truly haunting part is her features aren’t exaggerated to the point of diluting the revulsion. There’s no comical moles, no oversized noses and no sickly green skin common in witch interpretations. Too many horror films are spoiled by an embarrassingly exaggerated unveiling of the monster—think back to Insidious’ laughable demon, who looked more like a Bernie Sanders/Darth Maul hybrid than an otherworldly fiend. Viewers will long to alleviate the fright by writing off the witch as something grotesque and impossible, but Egger portrays her as just human enough to deny that comfort.

To fill the gaps left by the spotty glimpses of the witch, the movie relies heavily on sound and lighting. Whereas a period piece can falter with unrelatable conflicts and archaic dialogue, The Witch flawlessly tackles the genre. The film employs natural lighting, such as candlelit prayer sessions and lamp-guided excursions into the night, and the flickering ambience effortlessly transfers the terror from the protagonists to the audience. The 1630s setting and the family’s remoteness ensures there’s no shrill cellphone ringtones, passing cars or surprise guests to alleviate the tension with off-putting racket. If there isn’t a humming, encompassing instrumental score filling the air, the family is left in unrelenting silence. The only jarring aspect of the New England setting is the dialogue; it takes some getting used to, and some early conversations are troublesome to understand, but the persistency and dedication to the language will leave viewers fluent by the film’s conclusion.

The Witch’s conclusion is the only part that could’ve been improved. Approaching the film’s completion, there were several moments where it could’ve, and probably should’ve, ended, but it kept inching forwards. The ending was almost gratuitously supernatural to fit with the rest of the carefully subdued scenes, but it was the only appropriate finish for such a remarkably dark movie; it certainly didn’t take the easy way out. Given that the film was based upon actual writings and accounts from the time period, the dramatic finish is forgivable, and its execution and historical accuracy poses the question of whether there was any truth to the hocus-pocus, Salem witch trials and witch-hunting obsession of the era.