The Zombies (from left): Hugh Grundy, Chris White, Colin Blunstone, Rod Argent

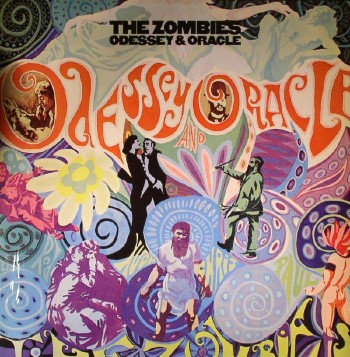

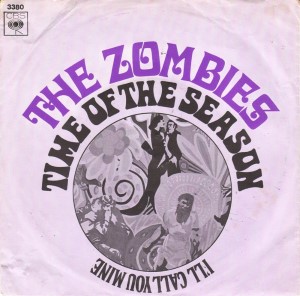

For youths in both America and England, the summer of 1967 was the time of the season for loving. A cultural movement had taken hold, fueled in part by pop music’s growing enlightenment and reflected in such landscape-changing hits as The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” (a prescient early entry released in late 1966) and The Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love.” Another earmark of the era is The Zombies’ now-classic “Time of the Season,” recorded in August of 1967 but not a hit until early ’69 (after the group had disbanded). It would appear on the English group’s swan song, Odessey and Oracle—“[an] album nobody wanted when it came out,” says founding Zombies bassist/songwriter Chris White. “That’s why The Zombies dissolved, really, basically.”

Odessey and Oracle (yes, “odyssey” is given an accidental alternate spelling in the album’s artwork) could just as appropriately have been named Oddity and Oracle, as this initial flop of an album went on to spark one of pop music’s strangest success stories. The once-obscure 1968 album has since been named number 100 in Rolling Stone’s Top 500 Albums list and currently sells more copies in each consecutive year. “Finding that other people [appreciate the album] that are younger than us, musicians especially . . . that’s the refreshing thing about it,” says White.

The record’s 50th anniversary reissue (celebrating its year of creation, not its release) has been coupled with a North American tour featuring the original quintet’s four surviving members, who will make a Nashville stop at TPAC on Sunday, April 9. This historic performance is one of the final opportunities to hear a live performance of the timeless Odessey and Oracle in its entirety—something that never happened during the original band’s 1961–68 lifespan.

White, who wrote seven of the album’s dozen tracks, tells the Pulse that the album’s material was written and recorded “in batches” between June and November of ’67. “We didn’t go in the studio for weeks on end,” he clarifies. “First of all we’d write a few songs, then we’d decide whether we all liked it at rehearsal, and then we’d book a session at the studio, like two- or three-hour sessions, to finish them.”

The first of those sessions took place on June 1, the very day The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released to unprecedented acclaim. “Sgt. Pepper had just finished recording when we went into the same [Abbey Road] studios,” notes White. “That’s why we used a Mellotron, because John Lennon had left his behind.”

Progressive technology such as the orchestra-simulating Mellotron and limited multi-track recording techniques were emerging in tandem with changing norms for the creation of pop and rock music, a climate that White explains was a major factor behind Odessey’s stylistic innovations. “Up to that point, I think the emphasis was on people going in recording singles and doing it quickly. But then of course, there was [The Beach Boys’] Pet Sounds, and then followed Sgt. Pepper, which followed Rubber Soul,” says White, referencing the groundbreaking string of artistically driven albums resulting from creative rivalry between The Beatles and Beach Boys musical visionary Brian Wilson.

“So,” continues White, “it was an exciting challenge not to write verse-chorus-middle eight [song formats]. We tried to make it different,” says White, “more like the structures The Beatles and Brian Wilson were doing.”

Contrasted with The Zombies’ British Invasion-era hit “She’s Not There” (itself boasting innovative chord changes and an unusually jazzy quality for its time), an artful progression in both lyrical and musical themes is evident on Odessey and Oracle. The album’s cuts straddle jaunty English music-hall stylings and elegant classicism alongside canny pop melodies and pioneering progressive-rock forms. Recognizable in White’s bittersweet “Beechwood Park” is the stately solemnity of Procol Harum’s 1967 breakthrough “Whiter Shade of Pale,” released just weeks before “Park” was put on tape, following keyboardist Rod Argent’s suggestion to veer in a direction comparable to “Pale.”

Argent’s wistfully lovely “A Rose for Emily,” inspired by the title of a short story by William Faulkner and affectingly sung by the incomparable Colin Blunstone, sensitively explored the plight of the elderly in a manner suggestive of The Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby.” But while clearly influenced by The Zombies’ similarly forward-looking peers, the album is a mature, innovative work that resembles other songs or artists only in fleeting and impressionistic ways. “Time of the Season,” for example, not only emerges as curiously unique for its time but also stands alone in The Zombies’ own small but solid body of work. Alternating a brooding, tribal core with an almost hymn-like choral turn, “Season” effectively concludes Odessey and Oracle with a fusion of the album’s darker and lighter hues.

Upon release, the striking and singularly sober “Butcher’s Tale (Western Front 1914)” seemed to speak to the then-peaking Vietnam War but in fact was the songwriter’s response to a World War I event that had touched his own family, its carnage becoming more concrete during White’s summer job as a butcher. “The real thing was my uncle who I’d never met―my mother told me―he was 16 years old and he was killed in the Battle of the Somme,” explains White, who would proceed to read books about the bloody event.

“All of a sudden one day I’m going to rehearsal and I suddenly had this vision, after I read it, of 60,000 casualties before breakfast on the first day of the battle,” remembers White. “The enormity, and the senselessness of it struck me; I had to drive the car to the side of the road and write down the verse, because it suddenly struck me how awful it was.”

The song’s harrowing drone was produced by an aged American pump organ of White’s that the band carried to the studio on the roof of their van. To reproduce the effect on their current tour, the band uses a similar but more portable instrument that bears a poignant connection to the unsettling genesis of “Butcher’s Tale”: an antique organ that, according to White, “was used by a chaplain in the First World War, on the battlefields.” (White admits that his sole difficulty performing Odessey’s original track sequence onstage is the emotional challenge of shifting immediately from “Butcher’s Tale” to the exuberantly romantic “Friends of Mine,” perhaps his sunniest composition from the album.)

Combat was otherwise the furthest thing from the minds of White and his bandmates while constructing the songs for Odessey. Conscription had ended in the early ’60s, freeing young Englishmen from required military service and, in a way, contributing to the youth revolution experienced in England later in the decade. “It was a freeing period, to be quite honest,” recalls White, “but it felt full of hope and excitement. It was a period of love and, for the English people, it was our coming out of rationing after [World War II], to be quite honest. Of course, it was the Summer of Love as well, which we all believed in at the time . . . and then [it was] corrupted into drugs and all sorts of terrible things.”

A particularly noteworthy feature of Odessey and Oracle is its sonic separation from hallucinogen-evoking studio trickery and the aurally dense, LSD-induced trappings of the “psychedelic era” with which the album is so closely identified. This connotation is far more apt for late-’60s works like Pink Floyd’s debut disc The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, weightier-sounding bands the likes of Iron Butterfly and The Electric Prunes, and the breed of improvisational dabblers typified by The Grateful Dead.

White understands the potential misnomer but displays an easy grasp of the distinction between the literal and more generalized applications of the term. “I think, basically, people use the expression ‘psychedelic’ of the period of the ’60s,” says White, “the same period of Pet Sounds and Sgt. Pepper. And psychedelic can also mean taking psychedelic drugs, which we didn’t; we were too innocent on that side. Psychedelia is of a period of art, [and] it can be taken that way when it refers to us.

“I think [creating Odessey and Oracle] was pure innocence and joy in the music,” concludes White. “It felt exactly right when we did it. It was of its time, it was done on four-track”—and bounced over to a second four-track machine, providing the band its first opportunity to overdub keyboards and elaborate vocal backings—“and when we finished it we thought it was the best we could have done at the time.”

The album’s economy, in terms both musical and financial, was—and still remains—a triumph. While The Beatles spent months of studio time and roughly £25,000 creating Sgt. Pepper, the commercially waning Zombies were given a mere £1,000, requiring intense pre-session preparation. The resulting album, despite its musical sophistication, possesses an overall simplicity and purity that may well account for its perennially fresh appeal, as well as making it possible to recreate it onstage (augmented by additional voices and, fittingly, Brian Wilson’s right-hand keyboard man, Darian Sahanaja).

“We try and make up for the overdubbing that we did,” says White of the expanded stage lineup. “It really is a thrill to play it. It just feels great, and great fun. We recreate the album, we play it all the way through. I’m still feeling like we’re in our twenties, or teenagers . . . except when we try to climb up stairs,” he says with a laugh. Even so, as White’s enthusiasm suggests, the music that emerged from the creatively fertile, love-and-peace-infused atmosphere of the late ’60s can still fend off the effects of time and the seasons.

“Our age has caught up with us, really, physically,” concedes White, now 74. “But onstage, it feels like we’re still those kids.”

~~

The Zombies will perform at TPAC at 7 p.m. Sunday, April 9; find tickets here.

Terrific article!

Comment April 6, 2017 @ 5:29 am

Great to hear the backstories! Looking forward to seeing the concert in Minneapolis!

Comment April 7, 2017 @ 1:08 am

Great article about a great band!!!

Comment April 7, 2017 @ 3:51 pm

Fabulous read. Love the info on songs and the part about White and Butchers Tale. As a late teens I like Brit Invasion and the Zombies but had little time for such songs. Years on, 33 to be exact, now I’m 51, such a song I realize was a daring inclusion and one of the most poignant yet gentle anti war songs.

Seeing them in Royal Oak, MI last week with my son, all these years later completed the circle. But only etched them and their music deeper within. Those songs resonated so strongly and flowed so fast. And Butchers Tale, the second verse as the organ started up again the crowd riard in appreciation of hearing something so vital. The song and Chris brought a concert hall of people to tears not unlike the end of the great 1957 movie “Paths of Glory”.

Thank you boys, and Paul in spirit(r.i.p)

M

Comment April 9, 2017 @ 3:31 pm