Ernest V. Stoneman’s 1926 recording of “The Sinking of the Titanic” on Edison Records Blue Amberol cylinder.

It’s almost impossible to imagine a time when pre-recorded music was not available, not part of our everyday lives and sonic environment. More and more people today get their music via streaming platforms, internet radio and other ephemeral sources, but those of us over a certain age remember growing up with physical music formats with fondness and nostalgia.

In recent years there’s been a rebirth of enthusiasm for vinyl and even some older tape formats, as many younger people have recognized that, despite the conveniences of streaming music, there’s still something missing: the artwork, the object itself, the simple ritual of placing the physical disc on the turntable.

The Center for Popular Music at MTSU, part of the College of Media and Entertainment, is one of the nation’s largest research archives of materials related to American popular music—the collection ranges from the 18th century to the present, covering every folk and commercial genre imaginable. Along with music books, sheet music, photographs, manuscripts and the like, sound recordings naturally make up a huge portion of the Center’s archival holdings, roughly 300,000 recordings in all.

This audio collection covers every format since the beginning, including all of the popular ones that were available to consumers, some that didn’t really catch on, and others only used by the music and radio industries. The archive also houses many examples of what’s referred to as “manuscript audio,” an oxymoronic term that means an original and one-of-a-kind recording usually made by an interviewer, field researcher or amateur musician.

Although there were some earlier experiments and breakthroughs, the invention of the phonograph sound recording machine is generally credited to Thomas Edison in 1877. Edison devised a way to capture the sound waves transmitted through the air, recording their vibrations onto cylinders wrapped in wax-covered paper or thin sheets of tinfoil. The recording and playback technology was entirely mechanical and acoustic, using no electricity.

Edison brought this technology to consumers starting in the late 1880s, originally marketing the phonograph for use as an office dictation machine. Soon he and others realized its potential for music and spoken-word entertainment. The cylinders began to be made of more durable compounds but the misnomer “wax cylinder” had stuck. Cylinders continued to be a viable commercial format well into the 1920s.

Around 1890 a German-born American inventor named Emile Berliner introduced a competing format, the flat platter disc, along with a new machine that he called by the brand name Gramophone. Although his first offerings were made of hard rubber, these discs evolved into what are generally called “seventy-eights,” 10-inch discs made of shellac that turn at a speed of 78 RPM (revolutions per minute). Shellac discs are relatively heavy and durable, but also brittle. They won’t warp, but if you drop one it will definitely break!

They are also limited to roughly three minutes per side, so they were sold as singles (one song per side). In the 1930s record companies began to sell some 78s in box sets called “albums,” with multiple discs in sleeves that the consumer would flip through. Some albums were devoted to big-name artists, while others were put together thematically (for example, “Cowboy Songs” or “Swinging Dance Music”). Album sets were also well-suited to longer classical or musical theater works. In addition, consumers could purchase empty albums to fill up with their own favorite discs, an early version of the personal playlist.

In the mid 1920s electrical recording technology began to replace the older acoustic recordings. Although cylinders and 78s were still the dominant formats, the sound quality of the recordings themselves improved as recording engineers began using microphones to capture sound electrically, yielding a wider dynamic range. Performance styles began to change as a result, with softer-voiced “crooners” like Bing Crosby able to take advantage of the new technology by singing into a mic at close proximity.

Vinyl discs came onto the scene in the late 1940s, both as 7-inch 45 RPM singles and as 12-inch 33⅓ LPs (“Long Playing”). The combination of a larger disc, a slower turntable speed and material that allowed more grooves per inch meant that LPs were able to get 15 or 20 minutes of music on each side; five or six songs instead of one. Since LPs collected multiple songs on one disc, they were still called “albums” even though the word was now used figuratively.

Twelve-inch album by The Perry County Music Makers from West Tennessee, released by Clarksville based Davis Unlimited in 1974.

Magnetic tape for sound recording appeared around the same time, in the immediate post-World War II years. Tape began to be used by the recording industry, opening the door to multi-track and overdubbing techniques in the studio.

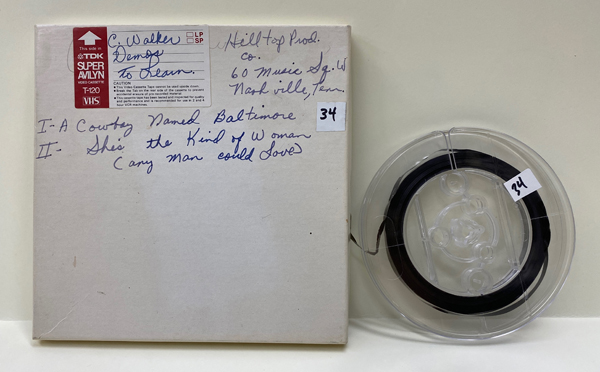

Five-inch open reel of quarter-inch magnetic tape, containing two “Demos to Learn” by country star Charlie Walker from the late 1960s

Soon various tape formats were marketed to consumers, as well. Many were on 5-, 7- or 10-inch open reels, but others were housed in cartridges to make their use easier. Though a viable consumer format, tape did not catch on in a big way until the more convenient 8-tracks and cassettes were introduced in the 1960s.

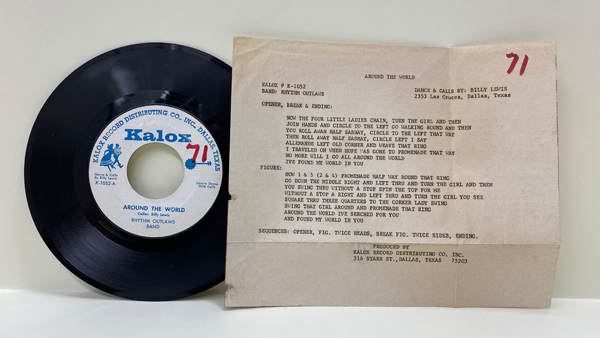

A square dance recording by the Rhythm Outlaws Band with caller Billy Lewis. Small regional labels throughout the country released square dance records like this in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Many came with a sheet of calls in the record sleeve.

Digital recordings and the CD (compact disc) format were the innovations of the 1980s. A completely new kind of recording and playback technology that converted continuous sound waves into binary digital information, digital recording offered even greater dynamic range, virtually no extraneous noise and the convenience of more than 70 minutes of music on one durable 5-inch disc. The downside for many, especially today’s advocates for analog vinyl media, is the perception that digital recordings sound hard-edged or “cold” when compared to vinyl recordings. Ultimately, as with anything sound related, the matter is subjective.

The Center for Popular Music holds thousands of recordings in each of these formats, and many more oddball or industry formats that most listeners have never seen. To give but one example, the Center’s collection includes roughly 2,500 large format 16-inch radio “transcription” discs, vinyl records that spin at 33⅓ RPM and were in use by the radio industry more than a decade before 12-inch vinyl LPs hit the market.

It seems clear that music streaming is here to stay, as most consumers value convenience and practically endless options at their fingertips, but the recent resurgence of interest in vinyl and even cassettes has made the music industry sit up and take notice. For a small but devoted segment of the music consumer marketplace, there will always be a demand to hold those beloved objects in their hands, and to have the gratifying pleasure of pressing “play” or dropping the needle.

FOR MORE on the Center for Popular Music, call 615-898-2449 or pay it a visit between 8:30 a.m. and 4 p.m. Monday—Friday in the MTSU Bragg Media and Entertainment Building.

[…] • Dr. Greg Reish, director of the Center for Popular Music, wrote an article about some of the center’s earliest examples of recorded sound for the June 1 Murfreesboro Pulse. The essay is available here. […]

Pingback June 3, 2021 @ 8:02 pm