Who is Felix Cavaliere?

Depending on whom you’re asking, the question is either entirely legitimate or ridiculously unnecessary.

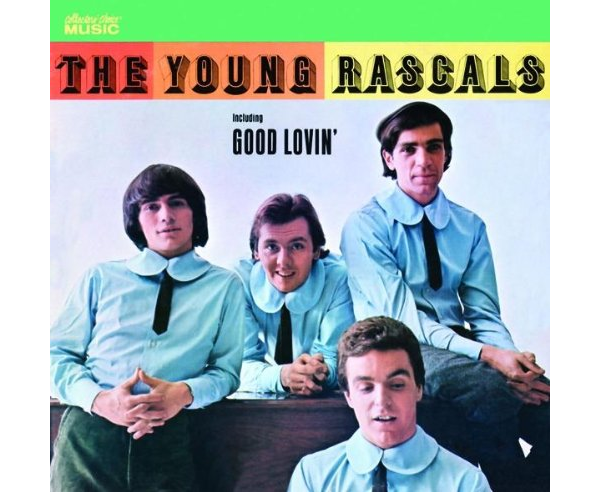

Anyone who attentively followed pop music made during the 1960s—either as a first-person observer or after the fact—should readily know the answer: Cavaliere is a highly regarded American musician, vocalist, songwriter and producer who co-founded Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees The Rascals. Initially billed as The Young Rascals for legal reasons, the quartet chalked up a total of nine Top 20 singles—among them the evergreen chart-toppers “Good Lovin’,” “Groovin'” and “People Got to Be Free.” Couple those culturally embedded hits with a soul-soaked voice and style as distinctive as his Italian-American moniker, and Cavaliere is a candidate for a household name . . . which he isn’t . . . quite.

For a variety of reasons—an apparently minimal appetite for notoriety being primary among them—the internationally known musician and songwriter lives a low-profile life in the Nashville area. With Cavaliere’s still-vital musical contributions deservedly bearing the collective name of The Rascals, despite his leading role, and his later work overshadowed by his band’s looming ’60s legacy, a younger generation might understandably shrug at the mention of his name. And that’s likely just fine with him.

Cavaliere, a Middle Tennessee resident since 1989, has in fact made himself available to the younger generation, freely offering encouragement and wisdom gained from his decades in music. Closer to home still, he’s a donor to Middle Tennessee State University, thanks to his longtime association with Ken Paulson, dean emeritus of MTSU’s College of Media and Entertainment. Paulson, now director of the Free Speech Center at MTSU, presented Cavaliere with the Free Speech in Music Award at MTSU’s Tucker Theatre earlier this year, in a presentation that included an onstage interview and concluded with a full-band concert featuring the evening’s honoree.

“Felix Cavaliere has always been on our short list to receive this award,” Paulson told the Pulse via email. He has used his free speech in music to inspire and entertain, and has supported causes he believes in for more than five decades. That’s exactly the kind of artist the Free Speech Center wants to recognize.

“Felix doesn’t talk a lot about the good work he’s done, but the MTSU College of Media and Entertainment knows firsthand his generosity,” Paulson added. “The gear he has donated shows up all over our college, and has benefited countless students seeking hands-on opportunities.”

In conversation with Cavaliere exclusively for this two-part Pulse feature, the respected musician expressed admiration for the music business courses offered at MTSU and nearby Belmont University. “In my time, if you wanted to get that type of education, you had to go and be an intern somewhere, in some studio. And it takes a long, long time that way. So I think it’s wonderful that this is available [locally] to the people who want to try this.”

Asked whether he thinks today’s technology is too convenient a substitute for a formal education or a hands-on, hard-knocks internship playing for an audience in clubs—and whether its prevalence could potentially rob tomorrow’s music of the quality and long shelf life demonstrated by his own work and that of others from his era—Cavaliere (who could be heard in the background stabbing at chords on a piano as he took the question in) offers a generous, teacherly response.

“There’s so many answers to that,” he begins in his distinctive outer-Bronx-bred accent. “For example, if you want to study art: Is it a good idea to go get some kind of an art education, so you know all the fundamentals of all the different media; for example, acrylic, or watercolor, oil? Or is it better just to go out and do a painting, sell a million copies of it? I always feel that the classical road, which is education and learning, is the best way,” says the musician, whose parents provided him with the opportunity—and, when necessary, a nudge toward discipline—for extensive musical training.

“Mom, she was an encourager, she made it possible. She—and my dad, of course—made it possible for me to study for eight years: piano, classical,” he explains. “And when I say ‘made it possible,’ I mean with a capital M. ‘You’re going. You’re going to practice, and you’re going to be there.’ And seriously, if she wasn’t that adamant and strong about it, I doubt I would have continued to learn at that level.”

Felix with Micky Dolenz of The Monkees (R), touring together on select dates

“And in terms of the music business,” Cavaliere continues, “when you go into the music world prepared for whatever—take for example, you’re a recording artist. Okay, so you have a hit record, and then you don’t have any more hit records. Okay. What if you have the ability or the talent to do arranging and producing? Now you can go make a whole new living,” Cavaliere notes, “without having to worry about having a hit record. You can make hit records for other people.

“So I’m all for education,” he concludes. “I think you cannot turn your back on that. Yeah, it’s easy to make a song on a computer, you know. Just like it’s easy to spell. Like with spellcheck, you just write it down and [it’ll] fix it for you. But do you know how to spell? No, you don’t!”

Cavaliere shifts to a more philosophical perspective when addressing his interviewer’s question about technology and the possible pitfalls of excessive dependence upon it. “The developments that are out there now, they’re pretty amazing,” Cavaliere says. “I studied for many years with a guru—a man by the name of Swami Satchidananda. He was the gentleman that opened up the [1969] Woodstock festival. And when people would ask him a similar question, he would say ‘Let’s take electricity, for an example. If you plug your iron in, it’s good; if you plug your finger in, it’s bad.’

“It’s kind of the same with . . . I mean, for example, during this pandemic, I had started an album prior to the lockdowns . . . and I was able to complete that album because of the technology, because of the internet, because of the computer programs. So, I think it’s a good thing, you know? But that’s a really good question . . . is that music gonna survive the test of time, like, for a silly example, ’Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer?’ I haven’t heard too many people trying to be around forever [with the music they’re creating]. I think the emphasis right now,” he reckons, “is on having a hit record, making a lot of money, and et cetera, et cetera.”

Cavaliere believes that universities offering music industry curricula like the programs at MTSU are vital for increasing one’s odds of success in today’s harder-than-ever music business. “That’s one of the things about these schools. They are emphasizing the relationship between business and music. You don’t get a hit record, man, unless you’ve got a good business team. And, unfortunately, now it’s even more important than the music,” Cavaliere says, noting that his own mistakes choosing business associates who “didn’t score so good in the management department” slowed his career momentum after The Rascals disbanded in 1972.

Felix Cavaliere performing. Photo by Leon Volskis

Ironically, while performing in early 20th-century schoolboy garb and recording as The Young Rascals at the outset of their hugely successful five-year run with Atlantic Records, the pseudo-adolescent band was in fact one of the most musically developed and creatively precocious to penetrate the then-erupting mid-’60s “beat group” scene. (Eventually, Cavaliere and his bandmates would ditch the novel but increasingly unhip kiddie costumes and legally regain their originally chosen name, The Rascals.) Cavaliere attributes the band’s early maturity largely to education—his own formal music and theory studies as well as his and his fellow Rascals’ intensive gigging practicum in a variety of settings prior to joining forces in 1964.

Cavaliere confesses that not even extensive training and performing fully prepared him for his first stint overseas, playing organ as a sideman for Joey Dee and the Starliters. A popular East Coast nightclub attraction, The Starliters had scored big in the early ’60s with “The Peppermint Twist,” a No. 1 U.S. hit that spawned a dance craze.

Wide-eyed at seeing the sights across the Big Pond, Cavaliere recalls, “Believe me . . . people would say to me ‘you’re gonna have to close your mouth’—because, I mean, I was like ‘wow! Wow!’ Wow!’—they said, ‘people are gonna think you’re an ashtray,’ because I was just in awe.

“I mean, first of all, come on, I’m going to Europe. We’re on those trains all the time. I’d read about this stuff, you know, and now I’m there, and we’re going across the sea, to Scandinavia, and the ice float. Man, I loved it,” Cavaliere says, his rising delivery conveying the exhilaration of those nearly 60-year-old recollections.

If that sounds exciting, well, you ain’t heard the half of it. It was on that European tour that the Starliters played a well-attended concert in Stockholm, Sweden. The hitmaking American band had drawn a crowd, but so had the opening act, a foursome from Liverpool, England, that had risen to the brink of fame in their native land.

“They were not known in the United States yet. That was soon to happen, I believe in ’64,” Cavaliere says of the band he and his fellow Starliters followed onstage that fall night in 1963. “But the enthusiasm and the excitement . . . enthusiasm really was an understatement. When they took the stage in this club . . . the place went bonkers. I mean, just bananas. I’d never seen anything like that, and certainly I had never been in a room with anything like that.”

And that, ladies and gents, is the story of the night Joey Dee and the Starliters’ audience was warmed up—some might say brought to a rolling boil—by The Beatles.

Next month, in the conclusion to this two-part feature, read about Felix Cavaliere’s inspirational introduction to The Beatles, highlights from his years as a Rascal, and commentary about music and the forces in and around its creation.

I’ve been surrounded by Felix as a club owner where Felix performed with a band other then the Rascals that originated in my Club in Garfield,NJ (Choo Choo Club).Felix excelled in every respect

In the music business and personal contacts we’ve had.Felix was definitely born to be super star. I’m his biggest fan as well as friends.

Comment June 4, 2022 @ 8:29 am