In last month’s edition of the Pulse, we answered the perhaps-obvious question “who is Felix Cavaliere?” Some readers, no doubt, were already well acquainted with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member, whose voice, songwriting and keyboard playing remain a primary fingerprint on the music of 1960s hitmakers The Young Rascals (later, simply The Rascals).

The first installment of this two-part feature included mention of Cavaliere’s MTSU appearance in February, when the longtime Nashville resident was honored with the Free Speech in Music Award, and concluded with the musician’s unforgettable introduction to The Beatles in October 1963, just months before the Liverpool quartet emerged as world-changers on the international stage. Here, Cavaliere continues describing the concert in Stockholm, Sweden, where the touring musician got a preview of the musical revolution about to unfold. Even more important, though, watching The Beatles enthrall an audience led Cavaliere to a moment of clarity about his own future.

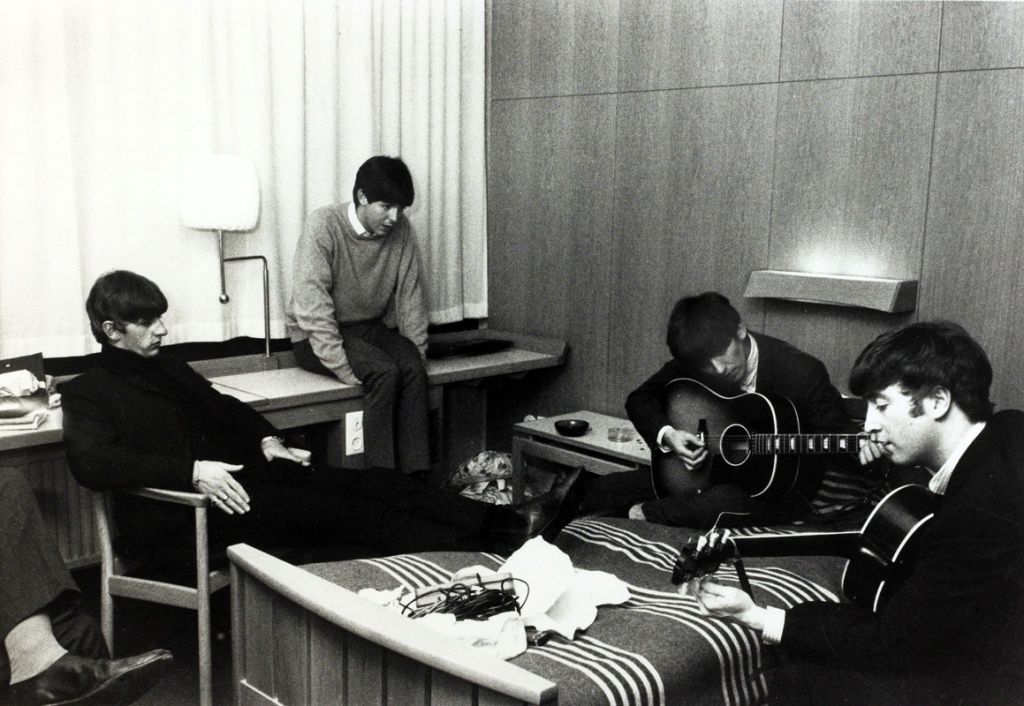

The Beatles use rare downtime in a Stockholm, Sweden hotel room in October 1963, before the scheduled pop-festival appearance where Felix Cavaliere learned of the English band’s existence (see poster below).

“So you look around and you say, ‘What’s going on here, what is this?” Cavaliere recalls. “And somebody says, ‘it’s The Beatles!’ And I said, ‘The what?’ (Laughs) “You can imagine the, the excitement that was in the room. So, as I listened to the music—I was at a turning point in my life, ‘cause I was just leaving school and embarking into the world. And I had to make a decision as to whether I should be in this business or not, in the music business.

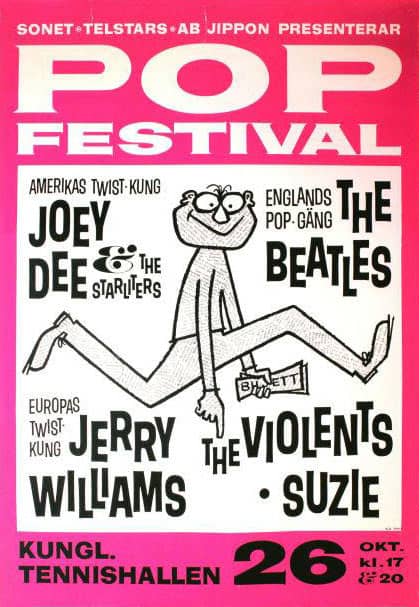

A poster for the 1963 Stockholm concert where Cavaliere, then a new member of the festival’s headlining American band, experienced The Beatles—and their ecstatic fans—for the first time

A Swedish fan crosses the stage line to grab George Harrison at The Beatles’ Oct. 26, 1963 performance in Stockholm. They were followed by Joey Dee & the Starliters, featuring Felix Cavaliere—then 18—on organ.

“Listening to them—excuse my naivete—but I thought ‘I can do that! I know what they’re doing. I can do that.’ I didn’t know [they would become] the most prolific writers of their generation, at the time,” Cavaliere clarifies. “But as a band? As a band, I said, hell, I can do that. I’m gonna put together a singing group, and a playing group, and we’re gonna conquer the world.”

Within a few years’ time, the musician had done exactly that.

Armed with the musical education Cavaliere described in part one of this story, he gave careful consideration to his choices for band mates, seeking maximum musicality and stage presence. Two of them, singer/percussionist Eddie Brigati and guitarist/singer Gene Cornish, were already on his radar as talented fellow members of the Starliters. Dino Danelli caught Cavaliere’s eye and ear as a skilled, locally gigging drummer following in the footsteps of jazz greats like Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich, musicians who had set the standard for drumming that was as dexterous as it was visually entertaining. Though Cavaliere is generally regarded as the band’s driving force, and rightly so, all four band members brought individual strengths inseparable from the whole of the music they would begin producing together.

After a series of false starts and transitional gigs, The Rascals began to jell as a club act in late 1964, debuting under that name in February ’65 and attracting interest from showbiz impresario Sid Bernstein, famed for booking The Beatles’ still-legendary Shea Stadium concerts. Somewhere around that time—and accounts differ—the band amended “Rascals” to “Young Rascals” to avoid legal entanglements with the name-trademarked, decades-old legacy group the Harmonica Rascals, formed in 1927 by a Russian immigrant who invented the chromatic harmonica. Widespread fame would later permit The Rascals to restore their original name in early ’68, though one might imagine that, in any case, no confusion would have been likely to ensue as to which band was which.

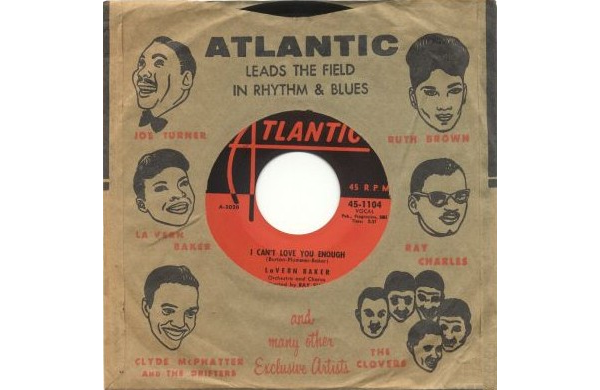

With talent, self-assurance and Bernstein’s professional clout, Cavaliere and his fellow Rascals made history as the first white act signed to Atlantic Records, a label specializing in the R&B music so formative to the band’s sound. Audaciously, they’d held out for an unprecedented record deal offering full artistic freedom, an accomplishment he brushes off as “basically stubbornness.” Cavaliere then softens, crediting the blessing of having a family that taught him to be self-assured, followed by the serendipity of having superb mentors firmly behind him and his band.

“The gift that I was given,” he concludes, “was A: to be confident that I could do it, or we could do it, and, second of all, when I went to Atlantic Records—which was the only purveyor that would give us control—they put two geniuses in the room with us,” Cavaliere says, referencing engineer Tom Dowd and producer Arif Mardin. These people are the top of the heap, and they’re in the same room with us,” he says with a hint of disbelief. “I mean, come on—you can’t fail with people like that. That’s the luck. That’s the gift.”

Cavaliere offers an example: the studio session that produced the band’s 1966 breakthrough hit “Good Lovin’,” a song previously honed into shape on nightclub stages. After one particular take, Cavaliere remembers returning to the control room with a suggestion. “I remember we were, in quotes, ‘in charge,’ and I’ll close that quote right there. I mean, we’re kids. And I walk in, big-shot Cavaliere, and I say, ‘You know, I think I can do that better.’ And Tom put his arms around the board and said, ‘You’re gonna have to go through me to do this again. That’s it, man. You guys just nailed it.’

“Okay, well, look, he was absolutely right,” Cavaliere admits. “‘Cause it was a number-one record almost instantly.” Cavaliere adds that he had great respect for Dowd “from the moment I walked in the door. I had every Atlantic record they made, and I saw his name on all of them. So I knew who this guy was, you know what I’m sayin’?’ (Laughs) And, as I say, anybody that really wants to learn about geniuses? Go look up Tom Dowd’s documentary. You’ll be amazed.”

“Good Lovin'” was a ticket not only to the top of the U.S. pop charts, but also straight to the stage of New York City’s storied Ed Sullivan Theater, where The Beatles had first mesmerized a record U.S. TV viewership—73 million—in February 1964. Cavaliere recounts the preparation that preceded the extremely popular, televised one-hour Ed Sullivan Show. “You started on Monday morning—early. You did rehearsals Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday. Saturday night in front of an audience. And then Sunday, it would go on the air, live . . . and we would do, what, maybe two minutes and 30 seconds?

“So now, here’s a group, young guys . . . energy up the yin-yang, going on after six days of rehearsals, for two minutes,” he says with a hearty laugh. “You’ve got a lot of energy built up for that two minutes, man, let me tell you. And when it hits, you explode. Wham!” The “wham!” is still intact in that Ed Sullivan clip, entirely worth the 2.5-minute watch. Notching up the tempo from the original recording, the band expels “Good Lovin'” with firehose-pressure power, all while wearing schoolboy costumes almost comically out of character with their aggressive, assured performance.

Unlike the earlier Sullivan appearances by The Beatles, originally a wild, unpredictable performing unit later groomed to semi-urbanity by manager Brian Epstein, The Rascals tear into “Good Lovin'” with an unrestrained physicality, Brigati kicking a leg outward and guitarist Cornish leaning into the three-chord hook, then momentarily crouching as though shoved backwards by the rhythm itself. Drummer Danelli is a muscular, stick-twirling machine, almost frighteningly compelling to watch; in mid-song, a cameraman fixes the lens on him in a close-up lasting an uncommonly generous 12 seconds.

Many of the bands that sprang forth in the wake of The Beatles were more intent on catching the British Invasion’s high-cresting wave of instant (and often fleeting) stardom than on necessarily making a lasting personal and musical statement. While some bands of the period obviously created music of substance, or at least left behind some now-nostalgic gems carrying an enduring charm, relatively few acts experiencing significant radio play and chart success in the mid-’60s staked out territory as distinctive and diverse as Cavaliere’s crew, whose streetwise, R&B-driven sound, especially at the outset, was thick-skinned and unapologetically American. It ran counter to the style of most Caucasian pop combos, and it made its own rules.

The Young Rascals’ self-titled debut album, while primarily composed of cover versions, is viewed by many as a standout album of the 1960s for its raw, white-soul bona fides. “Good Lovin'” was The Rascals’ reworking of The Olympics’ low-charting (No. 81) 1965 version (itself a songwriting upgrade of the underdeveloped and deservedly obscure original version). The Olympics, then a modestly successful, decade-old R&B act, offered a similarly engaging performance that clearly planted seeds soon to be harvested in The Rascals’ take. Theirs, though, carries a notable urgency that, for sheer impact, outstrips The Olympics’ more slickly produced version hands down.

Working from his authentic R&B roots and imaginatively utilizing the sounds and impressions of the ethnically mixed Manhattan-and-Bronx-area neighborhoods not much more than a police siren’s reach from the New York suburb where he was born and bred, primary composer Cavaliere would soon lead the charge in the Rascals’ evolution. The band’s third album, Groovin’, shifted to almost exclusively band-written material and signaled an increasing level of sophistication and stylistic progression. The No. 1 title track remains a vibey revelation, smartly produced and perennially pleasurable.

When presented with the suggestion that echoes of Cavaliere’s work can be heard in music that followed it, he turns reflective. “I think that’s what the business is supposed to be. You’re supposed to perpetuate it, and extend it, and . . . [The] Beatles, and Stones, followed Chuck Berry. I mean, Muddy Waters and all these guys, there’s a line.” Cavaliere speaks the truth here but perhaps downplays his own contribution to broadening the mainstream musical palette with a blend of R&B, jazz and Afro-Latin hues, even as he maintained his own original songwriting voice. One band in particular, the phenomenally successful, multicultural ’70s band War (creator of, among other hits, the ageless “Low Rider”), appears to have benefited from pursuing, and one-upping, the ethnic hybrid Cavaliere brought to mainstream ears in fresh form a few years prior.

When pressed regarding the strong similarity between the easygoing vibe of “Groovin'” and War’s early ’70s track “All Day Music,” both of which describe a laid-back weekend scenario while a winsome harmonica coos, Cavaliere restates his hand-me-down theory but allows that someone had been paying attention to his work. “I think we all paid attention to one another, it’s like a little fraternity where you’re all trying to impress one another. And emulate one another. It’s the coolest thing. You wanna sound like me? God bless you, man!” he says, completing his exclamation with a warm laugh. “It’s pretty cool. Pretty cool.”

Cavaliere’s current live version of “Groovin’,” one of the numbers featured at his Tucker Theatre performance earlier this year, seems designed to demonstrate in short form how music shares DNA in an ever-unfolding chain. Seamlessly sandwiched between halves of a nearly-seven-minute-long “Groovin'” are sections of similarly constructed R&B tunes from the same general time period: Jay & the Techniques’ 1967 Top 10 single “Apples, Peaches, Pumpkin Pie” and The Temptations’ 1971 hit “Just My Imagination” among them.

While Cavaliere’s recent invitation to MTSU to receive the Free Speech In Music Award speaks to his bighearted, ongoing philanthropic and humanitarian pursuits, the award also nods firmly toward the message contained in a particular Rascals track: the band’s final major hit, 1968’s “People Got to Be Free.” An almost unthinkably upbeat piece of social commentary coming in what may have been the decade’s most turbulent and tragedy-filled year, the song’s lyrics simply focused on the most generously unifying, non-controversial topic possible: the universal desire to live in freedom, experiencing a mutual exchange of respect and compassion.

The live version shown below, which aired in October 1970 on TV’s racially progressive Barbara McNair Show, is an impassioned rendering that includes a cover of the then-recent gospel-pop hit “Oh Happy Day,” with host McNair joining in. (The tightly produced, horn-buttressed original recording is required listening, though, for newcomers unfamiliar with it.)

In one of the musician’s very few furrowed-brow moments across a delightful hour-long conversation, he spoke out, in respect to his Free Speech in Music Award, about the restrictive climate for free expression darkening America today. “I think the word ‘freedom’ today, freedom of speech especially, is so abused, you know. But I think that what we’re talking about, seriously is one of the tenets of the United States of America. For want of a better word, that’s what defines our country—that you can say what you want.

“And I think in music it’s very important to be able to say what you want. But what disturbs me is when you say what you want and people get angry at you. I guess you can say and think what you want, but you better agree with me, or else, you know, I’m gonna cross you off my list. That bothers me,” Cavaliere concluded.

The politically inflamed touchiness Cavaliere references, so prevalent in 2022 America, simply emphasizes how relevant, and how sorely needed, the message of “People Got to Be Free” remains nearly 55 years later. Its verses gently challenge listeners, emphasizing how our basic, shared desires could, and should, result in easy and rewarding fellowship between folks of every color, creed and belief system. If it doesn’t transform the world in the end, the song does transform the three minutes it lasts, offering a tantalizing glimpse of something better, something almost possible to reach out and grasp.

Agreeing with the observation that “People Got to Be Free” was a peculiar model of protest song—one housing a joyful, inspirational message bereft of revolutionary rhetoric or dark proclamations—its co-writer turned to a big topic, one that provides context for the increasingly spiritual path that would inform the Rascals’ music as the ’60s began moving toward a close.

“You know, when music started, unless I’m mistaken, it was a tribute—a praise. They might not have had the right god, or gods, et cetera, but they were singing praise to the sun, or the planets . . . they were trying to reach that connection,” he begins. “And I really, really, really believe that that’s the only thing that really exists, not only from a musical point of view when you connect, but every religion has that connection. Catholics call it communing. . . . You wanna commune? Commune.

If you commune and connect, that channel is open . . . music comes through you. You would not believe it. And that is how I’ve lived my life,” Cavaliere says. “See, because we were taught [in church] about that connection. I’ve felt that connection. There is that connection. You want to connect? Connect, and see what happens.”

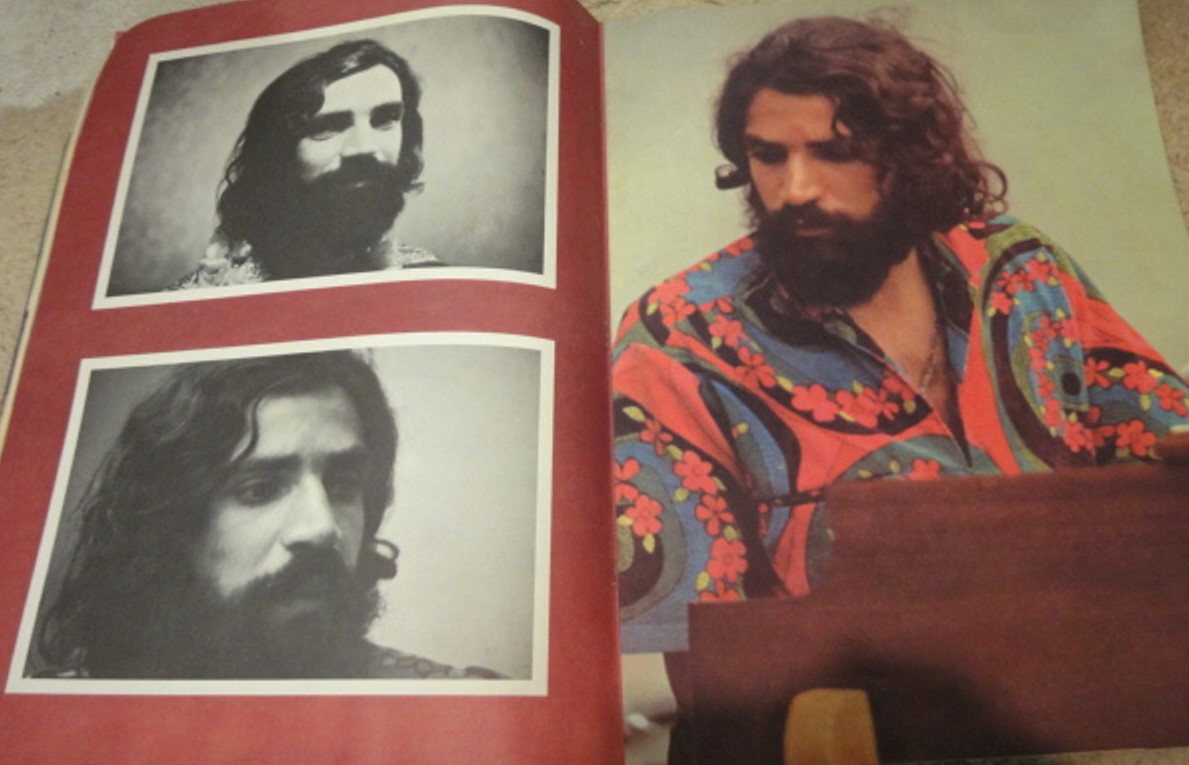

Cavaliere, pictured in a Rascals tour program from 1969, when his increasingly spiritual music began to find less favor with mainstream fans.

This spiritually informed approach to pop songwriting first peeked out from a Rascals single with the January 1967 release of “I’ve Been Lonely Too Long,” co-written with former Rascals band mate Eddie Brigati, who would complete the verses to songs launched from titles and choruses provided by Cavaliere. On “Lonely Too Long,” what could’ve been a garden-variety, romantically based lyric instead turned to the matter of mindset as the key to freeing individuals from whatever might diminish their capacity to make a fulfilling human connection (As I look back, I can see me lost and searching / Now I find that I can choose—I’m free!).

The psychedelic-garbed, high-energy “It’s Wonderful,, the band’s fourth 1967 single to reach or exceed the Top 20, was an open invitation to ecstatically embrace life, a concept appealing on paper but perhaps not one that the average Top 40 radio listener knew how to use. Next, the transcendent yet deceptively simple “A Beautiful Morning” repackaged the notion in a classic 1968 single that sits alongside “Groovin'” as a feelgood song for the ages.

After the chart-topping ’68 single “People Got to Be Free,” The Rascals’ attempts to further unfurl their wings creatively and explore inspirational themes (“Heaven,” “A Ray of Hope,” “See”) led, somewhat mystifyingly, to diminishing returns at radio and cash registers.

The Rascals’ original lineup then began to fray, leading to the revamped lineup’s official dissolution in 1972. Cavaliere rarely focuses on the past, or on his tribulations—which he frames as minor—and even his account of the bitter acrimony that took place among members of The Rascals winds up with a takeaway born of Cavaliere’s seemingly unsinkable attitude. “What I went through is a perfect example of how ego can destroy families, groups—there’s this relationship; jealousy, ego. It’s so silly. It’s something that I’m kind of embarrassed about, that my group broke up like that, ‘cause of stupidity like that,” he says. “But yeah—trials and tribulations, keep on goin’, man. Don’t let anything knock you down. That’s the answer.”

Currently performing as Felix Cavaliere’s Rascals, legal rights evidently still hounding him in the name department, the musician still makes, and experiences, the connection he finds so vital. And while he’s fast on his way to 80 years old, he says he benefits physically, mentally and spiritually from the disciplines he developed while seeking wisdom and holistic well-being through Eastern religion and Hatha Yoga beginning in the ’60s. In addition to Cavaliere’s gentle recommendation to “take care of your brain, your body, and your soul, and you’ll be okay,” he also cites his own church upbringing, presumably Catholic, as a valuable foundation.

“Like I say, if you have that as a basis—and I certainly had that; my mom would’ve gone to church eight days, but there were only seven—I think it makes a big difference. Because if nothing else, it just shows you that there’s a connection.

“And there’s definitely a connection. When we go to Japan,” he continues, “I know they don’t understand my words. But they know how it feels, and they know where it comes from. All over the world. Music may be our saving grace in this horrible time that we’re going through right now,” Cavaliere says. “It may be. We need something to save us, that’s for sure.”

(The recently released autobiography, Felix Cavaliere: Memoirs of a Rascal, is recommended for further reading.)

Steve….great piece, very behind the curtains with Felix. I have to disagree with Felix on one point though….freedom of speech is a two way freedom. Yes you have the right to say what you want, but responders have the right to disagree and reply . I had the picture in my head of Felix seeing the Beatles for the first time and saying ” hey , I can do that !’…..look closer Felix…:)….you can do some of that . The Rascals were great and I love the fusion of sounds and beats they used ….wonderful read Steve , keep it up !

Comment July 17, 2022 @ 8:39 pm